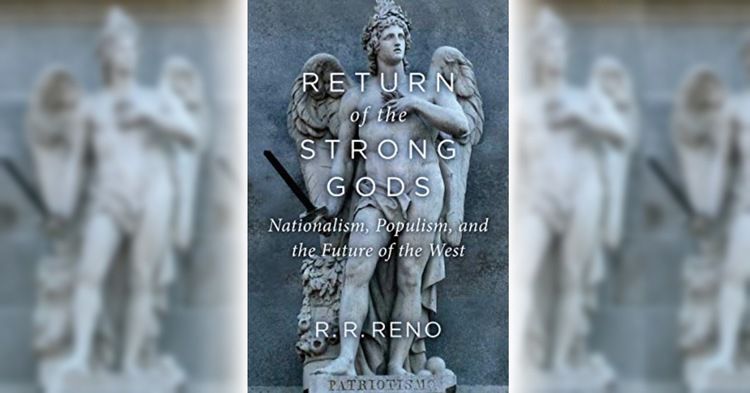

Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West, R.R. Reno; Gateway Editions, 2019, 208 pages

Allow me to begin this review by repeating my complaint about the “gutless persuasion,” which can be found in more detailed form in my editorial for the January issue of Chronicles. Contrary to the characterization of my late friend Sam Francis, I do not consider the “harmless persuasion” to be “harmless.” Rather, it is both gutless and vicious, gutless in the obsequious manner in which it serves sponsors and tries to accommodate the left, and vicious in the way it goes after dissenters on the right. A mostly bogus opposition to the PC left, the “gutless persuasion” is rarely serious about pushing back against its unscrupulous adversary, the main exceptions happening whenever it is time to appease ultra-Zionist sponsors and the arms industries.

"Exactly what effects have the Civil Rights revolution, feminism in all its phases, and the 'immigration reform' begun in the 1960s had on the American body politic? I’d like to know how Reno would answer these questions, although I doubt that he’d even try."

Thus Conservatism, Inc. collapses predictably on social issues, most recently on gay marriage and the desecration and/or removal of statues and plaques to onetime American heroes that offend the left. Even earlier this hopelessly compromised movement was affirming “second-wave feminism” and acclaiming the redemptive value of the civil rights revolution. So I wouldn’t be surprised if in the coming year Rich Lowry, David French, Jonah Goldberg, and Charlie Kirk came out for transgendered rest rooms and drag queen appearances in children’s libraries. Perhaps for the sake of balance, these pillars of conservative respectability might solemnly express provisional objections to male athletes participating in women’s sport events as females. They would then join the left in bashing anyone farther on the right for flirting with fascism.

Reading Russell Reno’s laments about the present age in Return of the Strong Gods, I was reminded of those who embrace this persuasion. Complaining about our late modernity while trying not to offend neoconservative gatekeepers and useful leftist allies is a difficult task. But Reno, as ever, is up to this challenge, just as Rich Lowry was in publishing a book on “nationalism” that never strayed from PC canons. The trick here is to address a provocative theme but to do so in a way that will not likely unsettle the left. Exemplifying this practice is Jonah Goldberg’s turgid tome Suicide of the West, whose title was ripped off from a far bolder book by James Burnham published in 1964. Although Goldberg manages to take positions on immigration, diversity, anti-racism, and so forth, which are diametrically opposed to those of Burnham, he still received plaudits from Conservatism, Inc. for supposedly updating Burnham’s trenchant critique of the left. In a similar manner, Reno has given us the approved conservative movement message regarding the need for community, without sounding unduly “nativist.” We are supposed to “love” our fellow-Americans, a throw-away line that Reno might have cribbed from Donald Trump, whose candidacy he emphatically resisted as a fashionable Never Trumper in 2016. Reno’s message also wins the approval of neocon Never Trumper Yuval Levin, whose influence Reno acknowledges and who blurbs his book. Not incidentally, Return of the Strong Gods comes to us courtesy of the Uber-Republican Regnery Gateway, a press that seems unlikely to hold Reno’s anti-Trump outbursts in 2016 against him.

Reno resists a familiar GOP talking point by abstaining from accusing the Democrats of being socialists or Marxists. The current left’s antiwhite-antimale-anti-Christian politics is clearly not a restatement of Marxist theory. Reno also seems to understand that there is a close link between the “open-culture” and “open-economy”; and he properly refers to those who combine these orientations as a “leadership class,” seeking “absolute power.” This class insists that only “they must rule.” “Otherwise we will slide back into stagnation, a closed economy of the oppression of a closed society.” Without these characters in charge we will “destroy our vibrant economy and the racists, xenophobes, and fascists will force women back into subservience and reestablish white supremacy.” Also, unlike other accredited members of Conservatism, Inc. Reno has read around a bit, so one encounters in his book appreciative references to Emile Durkheim, Ernst Jünger, Phillip Rieff, and other highbrow figures whom I doubt most Regnery authors would know by name.

Unfortunately, Reno also feels impelled to avoid difficult questions that his sponsors wouldn’t want him to touch. He writes about the power of the “strong gods,” those forces that hold us together (and divide us), which are far stronger than the appeal to “individual self-interest” on which liberal theory builds. He tells a poignant story about blacks and whites “coming together” in Church. That’s all very well and good, and like Reno, I support a religious revival in this country and in the West generally. Most blacks, however, continue to support the left, and that has dangerous cultural and moral as well as political implications. Exactly what effects have the Civil Rights revolution, feminism in all its phases, and the “immigration reform” begun in the 1960s had on the American body politic? I’d like to know how Reno would answer these questions, although I doubt that he’d even try.

Reno showcases his being invited to a conference at Yale celebrating the anniversary of Burnham’s Suicide of the West, for which the invitations (like those given for Yoram Hazony’s conference on national conservatism) were presumably handed out by neocon donors. But Reno’s PC reading of Burnham is not at all convincing. Regarding Burnham’s classic on the “contraction of the West,” Daniel McCarthy correctly observes at The Imaginative Conservative (October 11, 2018): “Where race and colonialism are concerned, Burnham’s Suicide reads in places like a bible for the alt-right. Liberalism, far from being something he wished to conserve, was for Burnham ‘the ideology of Western suicide’ —not the cause but a rationalization of the West’s waning will to live.” I would have to imagine that during the discussion in which Reno participated, Burnham’s “strong gods” were kept strictly out of view. I’ve also no idea how Reno intends to accommodate Burnham’s “strong gods” other than by calling for a “loving” American community and for the reading of a few more classics in college. It’s all quite vague. But, oh yes, Reno, a self-announced Catholic convert, does warn his readers against living in a “faithless society.”

Among the many examples of Reno’s eagerness to show his moderateness is his criticism of Aristotle for suggesting that democracies work best in small communities of like-minded citizens. Note that for Aristotle the polis is a form of self-government which he thought only Greeks could practice and which was characterized by the interchangeability of those who ruled and those who were ruled. But for Reno, “In Aristotle’s time, only the well-born few voted on laws. In modern democracies, by contrast, all citizens are implicated in the political process.” Reno also assures us: “Anyone who denies that a nation of more than 300 million people can practice democratic self-governance in any meaningful sense underestimates the power of the ‘we’. When seventy thousand football fans rise for the national anthem, their reverence is repaid with pride—pride in their country.” Reading these words in view of the virtue-signaling anti-Americanism that has marked the NFL in recent years, a phenomenon in which Colin Kaepernick is the representative figure, it is impossible to take Reno seriously.

Putting aside Reno’s identification of American solidarity with sports spectators, a connection that he and Rich Lowry both bring up in their latest books, it would be a good idea for Reno to take a crash course in ancient Athenian history. Because of the reforms of Solon, Cleisthenes, and Pericles, Athenian citizenship and voting rights were extremely widespread among those who were designated as “politai” (citizens). The critical distinction was between those who were citizens and those who were not, such as women, resident aliens, and slaves. Even Athenian-born day laborers (thetai) could hold citizenship, although not every position in the municipal government was open to those who did not pay a designated amount in taxes. I used to teach these and other esoteric facts about antiquity in first semester courses on Western civilization, but I doubt that Reno’s role as a leading member of Conservatism, Inc. requires him to learn such stuff.

Let me also note that what held together ancient democracies, and what Rousseau properly observed as their strength, was homonoia, a loyalty to the polity, its cult and its history. Today it is doubtful that our football fans embody the same shared sentiments. Reno fails to see that a democracy of, say, 10,000 citizens with the same cultural and moral principles wouldn’t practice self-government in a more meaningful sense than sports enthusiasts bellowing out the national anthem. Certainly, size and heterogeneity affect the quality of a democracy. Still, I wouldn’t expect Russell Reno to concede something so obvious, unless it were in his professional interest.