Home

It wasn’t heaven. Or maybe it was.

A heaven with a flaw in it.

Or several flaws. It’s devilish hard

To see what our parents saw in it

Now that potholes mottle the streets

And hypodermics strew

The skyscraper’s shadow like husks of wasps

At the foot of a wasted yew.

Unless our home was always this way,

Charcoal-sketched in mold,

The shingles soft to the roofer’s boot

For years before it sold,

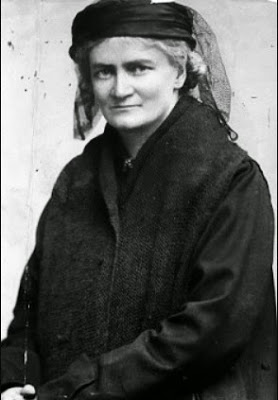

Our innocent parents, their English nascent,

Buying the seller’s story

And trusting all that they were told

About the founding glory.

Unless it is the trick of heaven

To be heavenly and flawed.

The eye test basement water stain

Distills the face of God

Or stays there, set in stone. To see

What is for what it isn’t,

The eye that does the seeing needs

The gift of distanced vision,

Soft focus on the aging diva,

Close but not too close,

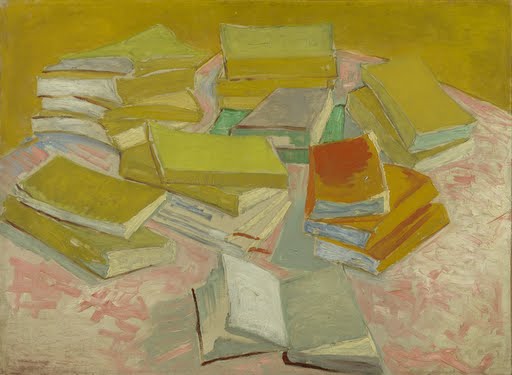

The words held far enough away,

No way to parse the prose.

From far enough away, the sky

Out West can mimic dawn,

But burning forests give a glow

To the smoke that says they’re gone.

The Rockies shrink at our approach

To a termite mound, a midden.

Every heaven needs a cloud

To keep the hellhole hidden.

Structural Engineering

A bone can bear more than a solid rod

The way a heart withstands for want of God.

The hollow hides the secret of its make.

The loss inside it means there’s less to break.

∞

No hand, no faith could hold for long without

A thumb to push back from below. No doubt

Five fingers grasp a thing beyond cognition

With four parts yes to one part opposition.

∞

The soles stay arched when the frame stands up.

A body flows along those aqueducts,

Two nooks for nothing ringed by strutting bones.

A body goes where bodies go alone.

∞

A flute, a throat is just a breathing hollow

That watches for its cue and plays its solo.

It’s really to the breath that songs belong,

And a breath is the wind’s and it’s already gone.

Washing the Corpses

They couldn’t touch us while they lived. But when

one died, the temple always called us in.

The Brahmins bathed their God in river water.

My grandmother—the last corpse-washer’s daughter,

the last to soap those bony yogis—strode,

her gangly arms out, right into the road.

The Brahmins, walking God home, stopped in horror.

Their sandalwood procession parted for her.

Once upon a time, the story opened

my eyes at bedtime, when our blood was soapscum

to holy men, those men too pure to touch

till they were dust. We didn’t work for much;

we worked for almonds, or we worked for ash,

our clients far too cleanly to handle cash.

From ash, we made more bars of soap. Our caste

had arts of its own. The vultures that we passed

took wing until we set our buckets down,

a private bodyguard to warn the town

that touched untouchables with bamboo canes.

I’m saying us, but I was born in Queens

where if I stick my hand out, anyone

might grab and shake it. “Once upon

a time,” my father says, “I thought I ought

to start a funeral home. But then I thought,

I came here, all the way here, to be new.

I’ll do whatever goddamn thing I do.”

My grandmother, the last corpse-washer’s daughter,

is telling all her dead about the water,

rubbing her ashen hands along her frame.

Almost bedtime. She greets her dead by name.

The water here, she sighs, so hot, so soft….

When I spread my arms, the soap just burns right off.