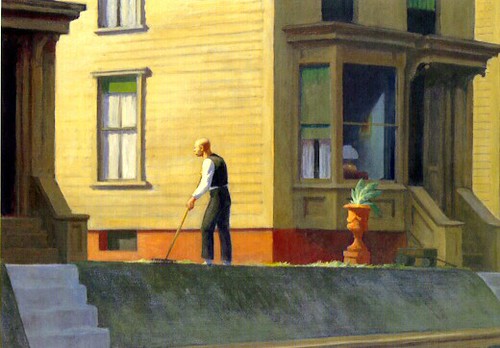

Edward Hopper’s Pennsylvania Coal Town

The patch town isn’t specified. It could

be one of many, like the nondescript

dwellings—all identical—of wood,

their little plots well-tended, borders clipped.

I spot a hobnail milk glass table lamp,

lace curtains, pictures on the parlor wall.

This relic of a former mining camp,

is mapped far from my home in Montreal.

Sunlight strikes a terra cotta urn

from which there sprouts a weather-beaten fern.

A man—the owner? renter?—takes a break

and looks at something far beyond my gaze.

The shadowed cart, the stationary rake

are faintly reminiscent of Millet’s

L’Angélus. But this man doesn’t bow

his head in prayer. He’s simply tired and hot.

Perhaps he’ll take a rag and wipe his brow,

resume his work without a second thought.

Or maybe, having had enough, undone,

he’ll curse the clapboard baking in the sun.

Fast forward fifty years. The man is dead.

Black diamonds blasted from the Northern Field

of ridge-and-valley Appalachia fed

our furnaces. All adits have been sealed.

Abandoned breakers loom above the town

that’s been declared the fourth worst place to live

in Pennsylvania. Life is tumbledown.

But this I know is true: that I would give

my eyeteeth for the chance to tell the man

in Hopper’s painting, Love it while you can.