Dry

“the dryness of his last years, which he so regretted.”

—Anthony Thwaite on Philip Larkin

Women go dry; men can’t get it up,

the spirit willing but the flesh too weak.

Their bodies differ, yet in poetry

there’s neither male nor female, Jew nor Greek.

Poets who have dried up see themselves

as empty-headed fools, figures of fun,

or pitiful hermaphrodites in whom

sterility and impotence are one.

Recognition of this altered state

comes slowly. Has our passion left us flat?

No messenger from Eros or the Muse

will tell us that the last time was just that.

Recent photos show us double-chinned

and slack, or pinched and rawboned, stooped with age.

Time at the desk yields only fits and starts

or else the pathos of an empty page.

Inevitably, memory recalls

the time before our gift began to wane.

The pool was overflowing and the act

no sooner finished than begun again.

Wisdom is the trade-off, so we like

to tell ourselves, for youth’s exuberance,

a wry corrective to those heady years

we thought ourselves the Muse’s fancy pants.

But wisdom brings the knowledge that we fail

so often, and it dogs us as we weigh

the latest effort, fearing to discover

that hours of work have ended in cliché.

A stately silence seems more dignified.

Better forget the poems we have penned

than toss another book onto that pile

of which, the Preacher says, there is no end.

Congealing from the leavings of self-doubt,

what surfaced as a vague disquiet hardens

into a certitude the wisest course

may simply be to cultivate our gardens.

And yet the only garden that we want

grew long ago. Desires wandered loose

as sporting panthers. Love rolled on its back,

while fruit splitting from ripeness dripped its juice,

and we were up for everything. Human,

we shared creation’s work. Each animal

came frisking to us, yearning for the name

that we alone could give. The act was all.

Then something happened, and we found ourselves

exiles in a dusty land with but

our hunger and the memory of a scent

that lingered outside after the gate was shut.

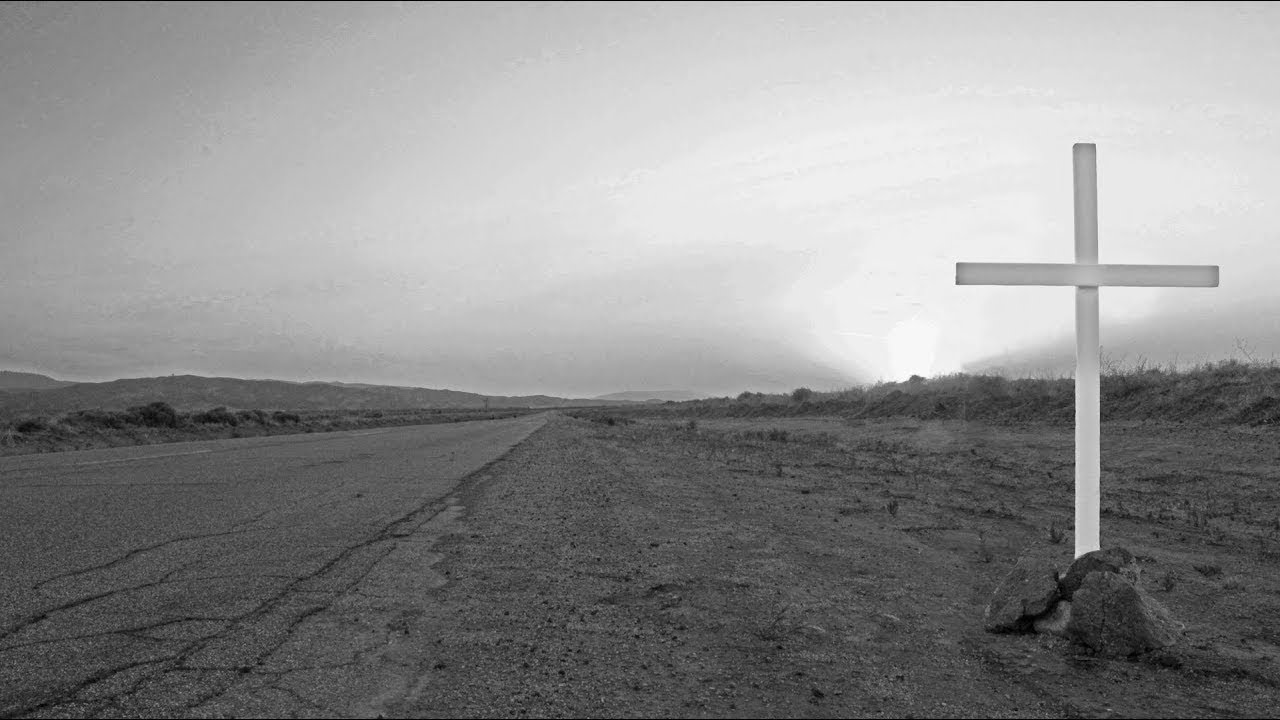

Crosses

After the bloodstained wrecks are towed away,

reports are filed, and funerals are held,

we sometimes see, like mushrooms after rain,

these humble roadside crosses springing up

amid the shards of glass and mangled bolts,

white-painted crossbars trussed or tacked together

and garlanded with artificial flowers.

Sometimes a name is daubed across the arms.

More often the dead remain anonymous,

and even with a name, how could we know

the truth of the one who died here, if he was

a faithful husband, loving father of three,

en route from a demanding late-shift job,

who skidded on an icy patch of road,

or the scapegrace sort with a suspended license

who called a boozy See-ya! to his pals

as the tavern closed and, staggering to his car,

went barreling off, his radio blaring, only

to miss a hairpin turn two miles away?

Irrelevant, to guess at saint or rascal—

somebody loved the dead enough to hazard

stopping on the highway’s narrow shoulder

and getting out to plant this small remembrance,

sometimes at serious peril. Near Fahnestock

on the Taconic Parkway, a white cross stands,

well up the rock face into which the driver

must have hurtled headlong. At what risk

did the person who installed it scale the slope,

chancing a fall as cars went whizzing by,

to wedge the cross securely in its crack?

Was he impelled by sentimental feelings

or haunted by the guilt of angry words

that sent the driver out into the dark

to death by accident or suicide?

Unauthorized, untended, they remain,

year after year, as no officious trooper

pulls them up. The orange-vested roadcrews

likewise mow around them as wildflowers

draw near to blend with faded plastic blooms.

Their white paint peels and weathers while the facts

that they denote lie elsewhere, weighted down

with granite headstones which, we surely know,

will long outlast these fragile sticks. And yet

as visits from bereaved survivors dwindle

to once or twice a year, and then to never,

headstones, unread by grieving eyes, become

anonymous as tree bark while these crosses

flicker in the memories of those

who pass them daily, modest evidence

of love and loss. And, finally, just love.