It was a muggy July morning as forty-year-old Dubliner, Jonathan “Johnnie” Driscoll cycled his way to work at Dublin Zoo, panting as he went up Infirmary Road. His second-hand mountain bike never felt heavier today as he felt the lactic acid burning in his legs. He suffered each morning on this short cycle. Jonathan had missed breakfast, and right now, had a hankering for a big juicy cheeseburger with lettuce, tomato, pickle and ketchup. At times he rubbed his right-side and winced at the memories of the pain which cavorted there from the infections caused by his addiction to junk food. Instead of just one biscuit, he would eat an entire packet in one sitting. He devoured ice-cream, chocolate bars, buns, cakes, custard, as well as cheeseburgers. So much so that he worried also about developing gout. He felt sharp pains in his stomach as though the shark fin soup he had ingested grew into a shark in his stomach after he had swallowed the last spoonful. Man boobs swelled from his sunken chest, which gave him a deflated look that left him feeling emasculated. Yet he persevered, and cycled painfully onwards, puffing painfully as he went. Last night’s curry still broiled away in his lower intestinal tract.

"He adored animals and simply could not bear it to see an animal in despair or suffering—any creature never mind how small, or, how big."

Stratus clouds had been building up in the morning, cluttering the sky in small white mounds. In his small flat, Jonathan had read the weather reports that the clouds would clear by midday day, bringing radiant sunshine in the afternoon. Now, beads of sweat dotted his forehead and glistened like summer rain on a window. Derek and the Domino’s Layla had just come on the radio via his smartphone, and he gave himself over to daydreams as the guitars came to a halt to open the passage for the solo piano.

*

His free time he spent compiling and editing Beyond the Dart. It was an online literary magazine that he had established two years ago with Ella Murphy, a platonic friend. It published the works of unknown Irish writers and artists.

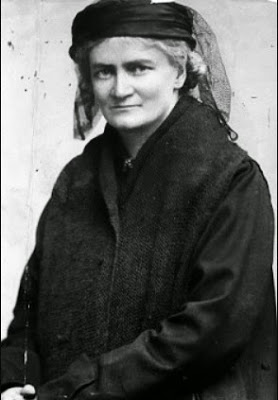

In the latest edition, included was an acrostic poem with the theme of naked rambling. Fig-shaped morality, Jonathan mused. He waited wistfully for a villanelle that had not yet arrived. He hoped some young poet would venture down the path blazed by Dylan Thomas and compose something for the ages. Also included were three short stories, photographs, and an essay on the subject of the poems written by Oscar Wilde’s mother under the pen name “Speranza.” Jonathan had an idea of his own for an essay about how quantum computers looked like religious relics with their gold accoutrements encased in glass sepulchres. Where science merges with Judeo-Christian iconography and objets d’art. The scallop-shell handles on his mahogany writing desk pleased him immensely. He had picked up this practical antique at O’Reilly’s Auction House, on Francis Street for 350 Euros. He sat behind it like a cat well-fed, purring over the submitted manuscripts.

Ella was into pottery and tapestries, but in literature, her tastes leaned toward detective fiction and anything “gory,” she would often say. But the current issue, the ninth one, featured nothing close to a good old-fashioned blood and guts murder mystery.

*

At the top of Infirmary Road, Jonathan turned left into Phoenix Park and on up past the bust of Sean Heuston, across the road from the Wellington Monument. The 203-foot high obelisk, nicknamed “the big Mickey” by the locals, towered over the landscape. Chinks of blue now expanded through the clouds, which dissipated and scattered toward the Dublin Mountains. It was now as hot as a summer day in Tuscany. Jonathan was drenched in sweat and his t-shirt stuck to his back and shoulders in the formation of a crucifix. He sighed and pulled the t-shirt away from his body, jiggling it to get some air to cool his sweaty torso.

*

Upon arriving at the Zoo, he showed his pass, as he did every morning. On the small plastic card was stamped Animal Welfare Officer. He then wheeled his bike in through the side-entrance and padlocked it to the railing beside his office at the amphibian house.

The smell of uric acid and ammonia overtook his nostrils as he passed the enclosure for the Chilean flamingos. In his research he learned that there were cave paintings in southern Spain of the pink birds that were over five thousand years old. He remembered that Lewis Carroll depicted them in Alice in Wonderland as croquet mallets. Twisting-preen, as they cleaned their pink plumage; and the splendour of seeing them sleeping while resting on one leg was almost magical. The umbrella curvature of their necks was fine to look upon, and their drooping cartoon-like beaks were comical. He sat down at the desk in his office to answer a slew of emails, usually benign, which awaited his replies each morning.

*

At the Ape House, a crowd of thirty people was staring at the five gorillas when one of them, an older male, got up, moved around, slowed to a stop, frowned and leapt towards the foot-thick glass and banged at it with his fists before bounding away. As thick grey ropes swung violently behind in his wake, the crowd drew back, shocked by this violent display. They could watch all kinds of violent acts on their wide-screen plasma-tellies but when faced with such a spectacle in the physical world, they turned into quivering husks of passive jelloids. They too hoovered up junk-food, like Jonathan, and had become incapacitated, and enslaved by the teeming abundance of the man-made matrix.

*

The phone rang. It was Ross McClure, the deputy manager of the Zoo. “Jonnie… we’ve had reports that one… of male the silver-backs… Herman… has been thumping the glass and is frightening the visitors,” he went on breathlessly.

“Herman? Wow…Okay, Ross, this is a worrisome start to the day.”

“It sure is, Jonnie, it sure is. I’ll leave it in your capable hands.”

Jonathan sighed deeply. He felt that he would not like to be gazed at through a thick glass window day after day and that Herman was only reacting to the absurd circumstances of his life. It was not normal. The gorilla rattling his cage had the soul of a starving artist demanding to be let out. He adored animals and simply could not bear it to see an animal in despair or suffering—any creature never mind how small, or, how big. He compared his own caging in the metropolis to the captivity of an enslaved animal lacking the ingenuity—or the opposable thumbs—to break out and get away. To at last attain the Rousseauian ideal of the totality of absolute freedom. He was bogged down by the demands of rising rents, skyrocketing bills, and the perverse economic system that made everything more expensive in the name of making everyone more free. The pupa of his frustrations began its fateful metamorphosis from idea to action: he concluded that a zoo is an organised prison which condemns the animals to slavery for the entertainment of human beings, who are themselves the captives of their own invisible cages.

“I’ll look into it, Ross.”

“Thanks…Johnnie.”

And at this moment, Jonathan decided to shake off the chrysalis of his conformity. He did not know what exactly he was doing but decided he had to do something. He walked out of his office, turned left and headed towards the security room, opening the door to the darkened inner sanctum with its banks of video-feed from the enclosures.

“Oh, hi, Johnnie,” Paudie the security officer greeted him as he walked in.

“Paudie, how’s the form? I just want to look at the Ape House to see what’s going on currently with Herman.”

“Oh, right, the Ape House, that would be up to your left. I haven’t noticed anything myself…” replied Paudie, whose gaze returned to the opened tabloid newspaper on the desk in front of him.

“I’ll just go here for a smoke, Jonnie,” Paudie said and went out to the sunshine.

Jonathan looked at his thumbnail, the flinty nimbus of his cuticle sired worry within him, it had a loamy dull white colour, the colour of an early demise.

He was fed up with the greediness of human beings. Taking a deep breath, he started hitting the release buttons for the enclosures.

*

The news soon came with footage of the animal breakout—a drone had caught a burly white rhinoceros thundering along Montpelier Hill in Stoneybatter towards the city centre. Over the next hour more reports came as the residents fled the city towards the countryside in their cars. The roads hummed with blaring horns and diesel fumes. A flange of baboons stormed through the Rotunda, driving out a gaggle of shrieking nurses. Ostriches nestled in the hospital alcoves. A tower of giraffes was reported at Mansion House eating the flowers from the baskets that hung across the façade of the building. Birds of paradise perched in the carriages of the Luas as they went slowly past. Abyssinian hornbills guarded the siding doors, barking at the Dublin patrons who tried to board the train. Peacocks roamed the platforms of Connolly Station. Stalled buses became a hang-out for the three-toed sloths gripping onto the vertical hand-rails. A Burmese python was attempting to coil its itself around the base of the millennium spire. Zebras rooted about in the long grasses in Phoenix Park. Eastern Bongos galloped past them towards the sweeter, leafier plants up at the Áras an Uachtaráin. Macaque monkeys were swinging on streetlights and signs. They threw their waste at the humans who were gawking as they bustled past. Penguins were swimming in the water in the Remembrance Garden. A pangolin trundled along Talbot Street sniffing at the bins.

Jonathan left the security office and was in the sunshine wondering his next move, then THACK! He was thumped on the back of the head by a silverback with a heavy wooden-stick and blacked out.

*

He came to with the sounds of a steamy forest and verdant canopy overhead. He was in the Greenhouse of the Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin. Past the sifting greens, there was red, like crushed red velvet, under his eyelids. A small, russet-coloured marmoset cheek-aboo-cheek-aboo looked at him and hoisted himself up a palm tree chee-chee-cheeing as it went. He heard the burbling of a radio. Impalas were reported on Moore Street. Jonathan made his way over there.

Outside a smallish Brazilian supermarket, two impalas were nosing at some squashed peaches under a wooden pallet. He tore apart a head of lettuce he found in a bin, and offered it to one of the creatures. It approached, hesitant but curious. It nibbled some of the iceberg lettuce, then tore off a larger piece and began to chew vigorously.

Suddenly, he heard an elephant trumpeting loudly from the direction of Trinity College. At a sports shop in the Jervis Centre, he entered and rooted around looking for protection. He tied cricketing gear around his legs and arms and snapped on a breast plate. Putting on a hurling helmet, he grabbed a hurley and emerged looking very much like a Thracian gladiator. But soon he felt hot and heavy, and decided to tear it all off, tossing aside even the stick.

Ferns had started growing on Pearse Street. Their fronds splayed radiant in the sun just like they did in the carboniferous period. River dolphins frolicked in the Liffey.

He sat down with his head in his hands and rubbed his face. He cried, he laughed. He looked around him, and noticed a piece of white-paper which was tucked into the side of the Luas track. Jonathan picked it up and opened to see what it contained, and therein was a child’s drawing in crayon. It depicted happy people with sunshine smiles, a massive dandelion, and big red shed. Lucy in the sky with diamonds. He smiled at the drawing as a tiger sneaked up behind him. The huge creature pounced upon him, and proceeded to sink its fangs into his soft and bulbous neck. Jonathan, initially, smiled, he did not waver—his rictus features clamping to a close as a golden eagle sailed past, its talons grasping a small, limp, furry mammal.

*

His prostate form lay on O’Connell Street as a phalanx of grey wolves loped along the tram tracks. Nearby, a tapir scratched itself against the Portland stone colonnade of the General Post Office. Its nose twitching in visual relief in the stately sunshine. Small, natty cravats of ivy crept up the pillars. A simian yawned and scratched its stomach in the porch of a restaurant on Upper Baggot street. In Temple Bar, camels brayed at each other. On Talbot Street, the pangolin pawed and sniffed at half-a-spelt lemon muffin. Thousands of butterflies emerged from their pods stitching bright colours in the summer air on Capel Street. A brilliant scarlet ibis looked out from the top of Parnell’s monument and squawked through the annals of all existence. The grasslands of Santry and Tallaght hid crocodiles and snapping turtles that waddled into ponds and sitting water. A steamy ecological system again took a firm hold.

*

All over Dublin the readapted wild animals attacked the few remaining residents with abandon. Panthers leapt from trees, and balconies, onto fleeing residents. Elephants stampeded those last few remaining Dubliners who were unwise enough to stay around for the slaughter. It was almost ritualistic and cleansing. It was as if the animals could understand how ugly the world had become under man and had come back to reclaim the planet.