This is about becoming a father, so it begins with Barack Obama. A week before the 2008 Democratic Primary of South Carolina, K stands in the cold and awaits the candidate’s speech at Clemson. He is high above the lower amphitheater, apart from the crowd. Indeed, there could be thousands below him, young Southerners in search of unity. Or celebrity, some politics of inclusion, an American link to today’s Africa. A smart, cool black guy in their circle of friends. Together, he thinks, we want to feel there is hope. Those of us above the fray, intent on maintaining our peripheral status, stand apart from each other as well. K turns to observe his fellow countrymen, the people he lives among in the foothills of the Blue Ridge. The various souls of Clemson, South Carolina.

"He is going to ensure that every Bolaño in these great states is granted the gift of affordable health coverage. We will nurture and encourage all dishwashers from sea to shining sea; our position on immigrants though will remain as vague as possible, tentatively, until at least the general election."

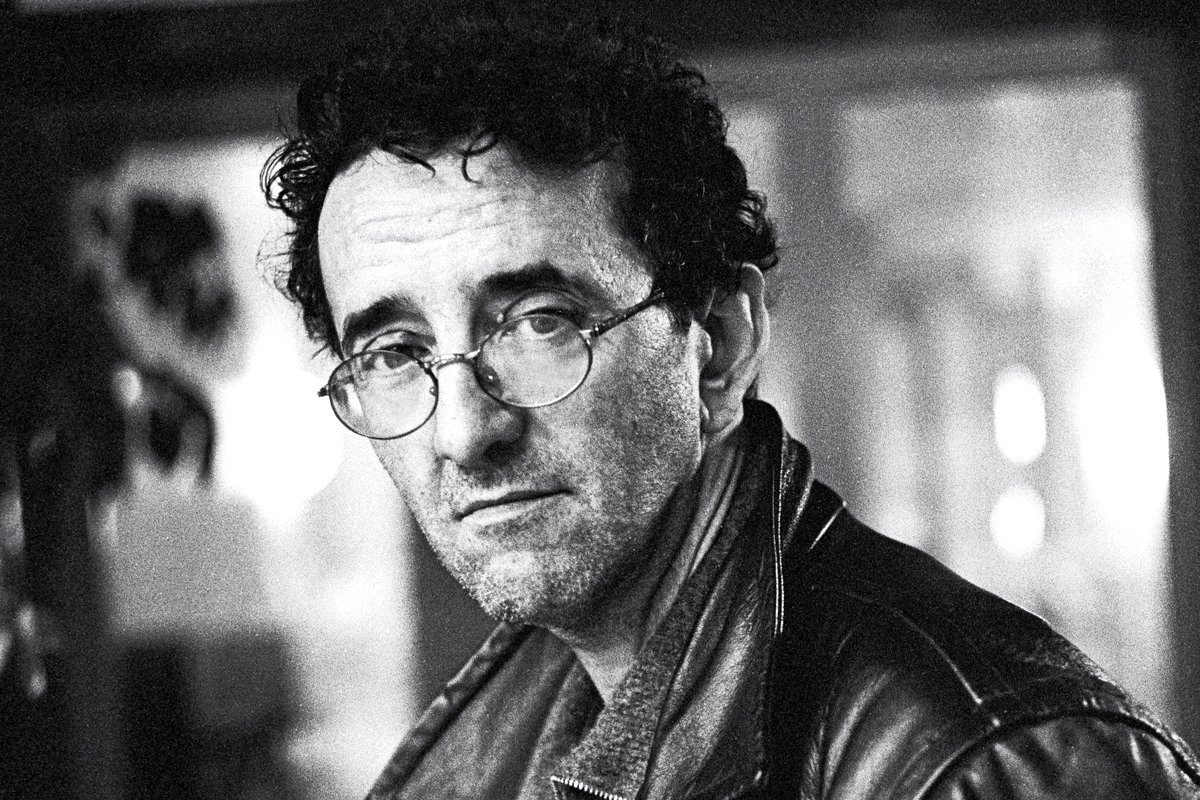

The gentleman who stands out is twenty yards to K’s left. He is there with a thick grey tunic over multiple layers of sweater, shirt, and underwear. His large backpack lies in front of him on the brownish dead grass of late January. He wears no hat or hood, and K can see he has a weathered tan skin and scruffy black locks. No balding at all and yet, he can tell the man is a bit older but no more than half a generation north. But the man is worn, seasoned. And it may be because of all the fresh translation that burns itself into the brain of Anglophones like K—reading him for the first time—or it may just be the man’s slightly Iberian features. K cannot say for sure how or why, but the man resembles how K imagines Roberto Bolaño. A loner. A backpacker. K knows there is a notebook and pen in that large sack; there must be a dog-eared copy of some poetry or a novel. K needs to imagine this man as Bolaño.

Before Obama arrives—to bring K together with the others, even those who stand on the furthest fringe—K realizes he has crossed paths with Bolaño once before. He met the author while competing for dishwasher work in an outer arrondisement of Paris. It is clear to K now. This was the summer of 1989. He was close to la banlieue, but it was definitely Paris. He smelled no burning rubber; he saw no cars on fire. The city of lights. Salut, Paris.

K was looking for work with six months left of the 1980s, and he watched as two others tried to get the job of dishwasher, un plongeur, at a seafood joint a bit off the beaten tourist track. The décor there was two-toned—sky blue and turquoise. It was intense how the one man lobbied so ferociously; it took K a minute or two to understand the lobbyist was fighting on his friend’s behalf. And his friend was none other than Roberto Bolaño. (It had to be, in these altered and edited versions of all of our lives and times.) It was late in Bolaño’s bohemian life. In the action of The Savage Detectives, Arturo Belano, his alter ego, performs menial labor in the seventies or eighties—campsite guard or fishing boat for his friend Ulises Lima. Maybe it was three or 13 years later, but the real Bolaño still required un boulot. This kind of work. A “slave,” yes, for sustenance, because Bolaño was lean. K was twenty years younger but twenty pounds heavier. The privilege of North American beef and power versus what we imposed upon his country, his Latino beans and exile? Perhaps his fatigue from malnutrition prevented him from fighting his own battle that day; rather, his friend pursued a scratch of work from food scraps for the covert genius. He fought not only for the poet, but for poetry. This was before his novelist’s tear of the 1990s. Never mind the English translations that would arrive for the most part after the millennium. What K would read, how K would learn. This was Bolaño, tout de pres aux faire la vaiselle.

There K was too, in very bad French, and with only some journaling and letter writing to his name. 20 years old. Time off from college. Watching and waiting. And then his turn came and K was offered the job. For 4,000 francs a month, at the time less than 700 dollars. Had Bolaño been seeking a legitimate salary? Had he refused this paltry wages and no benefits package? Had he been rejected due to his age? Eager youth and illiterates only need apply. Or had he been aiming higher? Going for waiter? Garcon Bolaño, s’il vous plait. A great bartender would have been Roberto.

It all makes sense now, that this was the writer whom K witnessed fighting for his meager allowance. If K had known about life and the endurance it would require; if K had known about living literature, he could have offered the great man a steady flop, a bed, half of what he needed.

“Hey, Roberto, you come stay with me. On the floor, in my place, or what the heck, we will sleep in the bed together, head to toe. I will go out and wash dishes. Parisian supermarkets are expensive, but I’ll put some baguette on the table. Some yogurt in the icebox, some chamomile tea in the kettle. You stay home and write and become Bolaño. Go to a library if you need to get out.”

Yes, that is something K could have said. Or, this:

“Think of it this way, the young American repaying Chile for what his countrymen Nixon and Kissinger did—19 years later, and no, I don’t believe a word I hear about the success of their privatized social-security system. It is all bunk—just Fox News propaganda. I will act the young American all over again—privileged and innocent and certain we can improve and progress; we will make it all right in a second or fifth coming.”

Yet K said nothing. He let Bolaño walk. He went in the back alone and saw the menacing grime and porcelain that could be his life for under seven hundred a month in converted U.S. dollars.

But a fleeting witness to greatness K was on that day in late June 1989. Bolaño retired to his Jardin du Luxembourg, and K left that restaurant and never returned. He met a high school classmate who worked in the Burger King on the Champs-Elysees, and within a week he’d become a busboy—un commis—in a Pizza Del Arte by Place de l’Opera and American Express. So neither of us ever washed dishes at that fish joint, neither had the chance to rule from behind the scenes, as a backstage operator, to put in charge a puppet regime and pull strings attached to the maître d’.

K was at the beginning point of his own malaise of a “writing life.” Bolaño was due to take off; the wall was collapsing; K was scared and too tired to visit Eastern Europe that fall. Indeed, he was the perfect gringo. American. Americano. He felt that Bolaño ignored him, but had he caught the great man’s eye, K was certain he would have acknowledged his humanity all the same. It was their fate to cross paths in ’89.

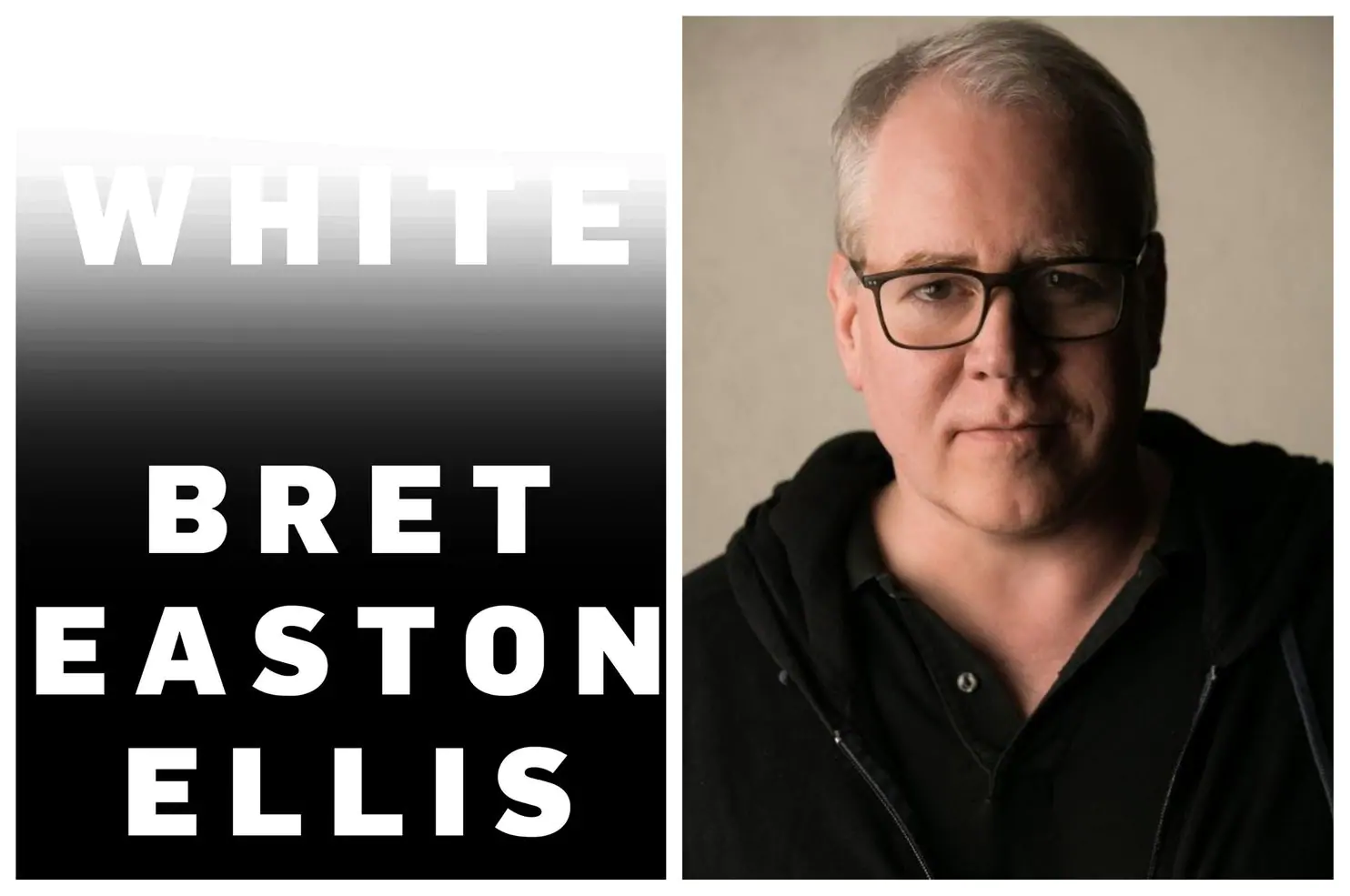

Nearly 19 years later, K will walk into a Clemson classroom and attempt to teach Distant Star. Somehow, K will tell them of Pinochet and Nixon and Kissinger and perhaps even connect all that trouble to Law and Order. He will tell them of the young loyal conservative lawyer Fred Thompson who chose MLK Day 2008 to quit the race; now they call it the most depressing day of the calendar, as if anything had changed. In class, hopefully, we can make sense of it all. In a 50-minute session, we’ll tidy up all the world’s angst and pain and leave invigorated and pleased with ourselves.

But because K is derivative and distancing bullshit, and it was me, not K, I’ll pile on by talking about the gulags and camps of communist societies. I’ll shout out that “an injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere!” Then, I’ll tell them it was Martin even if it was Malcolm. I’ll confess to a thick over-representation in my portfolio of the S&P 500 and make fun of the absurd tenured radicals who don’t know how their funds for old age devour our world. There’s no Kerouac out there; all that’s left is a bunch of corporatist henchmen funding their retirements through student loans and the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America-College Retirement Equities Fund. Killing their darlings, debt-slaving the children, but fish stench or no, student futures are washed down the drain. Left-wing, my ass, aye, that’s what Bolaño is saying on pages 93 and 27 and 113. At least he knew to write it all down when he could afford some scraps of paper.

And in effigy we’ll burn a paper copy of “The Singer Solution to World Poverty.” Fuck his tenured ass, too, for getting anthologized in a Best of for that crap. Who the hell can give up a third of his salary? He didn’t even mention our wage-to-debt ratios or the taxes we pay on our hard-earned, middling-class dollars—federal, local, property plus cable. Did he consider before he wrote it that the American worker has no job security? That we’re broke and losing a third already?

But then we’ll cry as we look at slides of Louis Kahn’s capital; its proof of the beneficence of the American spirit. We’ll journey to the tired and poor and hungry of Bangladesh and, thanks to the architect, we’ll supplicate and pray for forgiveness. And warn the children of how the great man was a bad father. Bad father, bad. From the classroom, we’ll call long distance, on our cell phones, to try to reach out to Bolaño’s son or daughter. “We’re from the land of Yankee, Oil, and Bush.” We’ll whisper into the phone and wait for the truth.

Yes, back to Bolaño and “The Eye” and “Anne Moore’s Life” and everything else that is gruesome and beautiful in this world. The students will gather their belongings, and leave puzzled if not just as apathetic as when they came in. A few will enjoy the show. Some will call it boring because they find it depressing; others will call it boring because they find it unbearable. Who knows what the fuck the lecture was about anyway? Like dude was rambling. A few will get the jokes; a few will question what, if anything, they’ve learned. One or two will try to twist it into something that could earn them a dollar. They’re polite and decent, focused young Southerners, so no one will complain as long as generosity accompanies their grades.

I am roused from this deep reverie by the words of the Presidential candidate, Barack Hussein Obama. He is here now, offering jobs and a strengthened social-safety net. The real Obama, not a scruffy-backpacker lookalike, and he enables us to forget it all for a moment. To join with him; to be together. His speaking is loud and crisp, a perfect complement to late-afternoon winter and the declining sun. The sum of his speech is that we are a nation of good people. Our national wounds can heal; we can be saved. He is going to ensure that every Bolaño in these great states is granted the gift of affordable health coverage. We will nurture and encourage all dishwashers from sea to shining sea; our position on immigrants though will remain as vague as possible, tentatively, until at least the general election. Does Obama care that Arturo Belano may have been an illegal?

We will not remember the latent misogyny moving us away from voting for Hillary; we will not see Israel as imperialist or America as capitalist or pro-Tibet as hypocrisy; we will not see slavery or internment or our disability or unemployment or any other kind of injustice. The black friend we were all denied, Pynchon’s secret integration, yeah, the rest of it.

Nor will we connect any sort of slum-lording to our own life, not even if it paid our college tuition. Not one thread of truth can ruin this intoxicating vision Obama exhorts us to share. “Hope” and “unity” and “one America” and the finale, “We can change the world.”

Exhilarating, blinding, and overwhelming. So I return to hiding behind K—even K must admit that much. Obama is a dreamer, but K is with him and the crowd, collectively hallucinating. Yes. Obama is no different from Bolaño. Obama. Bolaño. Three syllables each, their names turn each other around, like the opposite sides of a reversible jacket. Not so much a jacket as much as an overcoat, like the dark quality wool threads of Barack Hussein Obama, Chicago Barach, political maker and shaker in the city of Italian beef sandwiches and deep-dish pizza. Here to wave his big tan dick and bring peace, not war, to the world.

Baruch Ata Ado-nai

Elo-hanu Melech Haolam

Blessed are You, Lord our God,

King of the universe,

Who has sanctified us with His commandments,

And commanded us concerning the washing of the hands before we eat our Christmas Chinese.

God damn! If it’s not all coming full circle, I’m an insane instigator who can’t stay away.

But yeah, like El Presidente was wearing fine but thin threads on the stage in this late January, Clemson cold. From far away, I cannot see whether he shivers, but I have heard you can father the boy outside of Africa but you can’t take the father’s Africa out of the boy. To many the middle name is Muslim, but I recognize the first name as Jewish. Like Bolaño, Obama is a king of peace; he brings the Muslims and the Jews together. And it is true, I feel it! And shed tears. Yippee and yay! We can change the world, we can change the world. The soul of Bolaño is alive in Obama!

I return home in a rush of emotion, unsure as to whether the hundreds of international grad students crammed with me on the public bus are coming from the rally or merely returning from their daily exploitation, their twelve-hour “opportunity” in a lab at an American university. But they are chatting and smiling and I feel as if Bolaño’s spirit is in the air. Barack is only the messenger, but for a few hours at least, Clemson will be alive with this infectious Obama. I gasp for air but suppress the need to vomit while smushed against this crowded shuttle bus of hard workers and high-test scorers, not so freshly arrived from foreign cultures where, unlike domestic careerists, people don’t regularly scrub themselves immaculate. Could they be rich kids who paid for a Shanghai stand-in to take the test?

At the kitchen table, I explain everything to the woman from Xi’an, China, the one with whom I have conceived a child, the woman who told me I could not conceive of the poverty, the hunger, I could see in China today. In the comfort of my living room, no matter how old the furniture, Bolaño’s “The Eye” is great reading. It is literature. The children are saved, at least while they’re reading. But in China I would cringe; my eyes would look away. I would not be able to stand it. Weak, spoiled American male that I am. A heat-wasting, cable-watching, five-dollar-coffee-buying conceited and lazy motherfucker.

Yeah, always, in my culture, we need to make love to the mother. Smoochies, mom! All this before the yellow bitch don’t take the slot with spouse hire. Did I tell you brother K ain’t get laid since he make baby? Is that why Berlin K had to snag his young cousin? Woah. Ouch. Oh? Pardon. I beg your pardon. Back to me. Fuck K, that henpecked asswipe. Back to dinner.

My wife does not describe the distended stomachs we associate with Ethiopia. Indeed, she does not describe Chinese want or scarcity at all. But what she says looms over our shared dishes, and I know it would out-Bolaño anything from Latin America described by Che or Ariel or Hugo or Fidel or any other lefty Latin American leaders no matter how ridiculous, power-craving, or hypocritical. What is worse, I ask you, assuming a tenured post at Duke, a slot in the military-athletic complex of big-time sports campuses? Or giving the gift of home heating oil to poor families in the United States, on behalf of the people of Venezuela, while poverty swallows whole communities among one’s own? The Chinese Jews were never good Marxists, and Bolaño was hardly a voter, never mind a pious socialist.

Ugh!

It is too much. Too confusing and absurd for anyone, never mind a bloated, red-blooded American, to waste time on such convolutions. Better to imagine the meeting with Bolaño. In my revised telling to the Chinese woman, previously depicted as carrying our child, they took us both. Bolaño need not rush off with his lobbyist; rather, he was hired with me. So yes, what happened was that they took us both in the back, to the dishes, the dirty ones ready to be processed through a huge steel dish-washing machine. It stunk like rotten eggs and oil-slick sea life. Yes, I should call it ocean death. They gave us massive black rubber gloves that covered our arms all the way to the elbow.

Arturo moved ahead of me. He got down on his knees. I thought he was going to pray on behalf of every dirty dish near and far, but instead he picked up a saucer and some brown and sallow food scraps from underneath the machine. Ah, an eye for detail. Like Joyce. Like Proust. And then he rose. Removed from the murkiest depths of the soaking dishes a wide water glass and clutched it to his breasts, as if he were holding a sacred chalice. He lifted it to his lips, and drank. He drank for the poor dishwashers all over the world, and the émigré writers and the starving peasants who’d gladly consume potato scraps from any of this Parisian discard. He drank for Presidential hopefuls to be, for all those around the world who ever tasted the intoxicating liquor of hope and change.

Back to now in Clemson, South Carolina, I swallow my food and gulp for air and remember I am writing this story before I have walked off, gone vagabond away from a woman and child. Yeah, I could slip the lock, sneak out, and escape to San Fran with most of my hair. I’d lose twenty pounds and cruise the Starbucks scene in the Castro district. I’d pass as rough trade and live happily ever after. Alone. They’d say K ditched like a fuck-up, a famous storyteller, or worse. I give you Saul Bellow, Jack Kerouac, Fred Exley, Sherwood Anderson, and all the cowardly literary fathers. The great American writers. No? Wrong country or continent? A canon full of fascist sympathizers, and you give me our saintly Bolaño. Lived with his wife and children for twenty-two years? Did he bolt too? No cojones when it counted? You tell me. You decide.

But back to now, I’m so far gone that I do not notice that the Chinese woman is staring at me because there’s gristle stuck in my teeth, and I’m waving my chopsticks around like a lunatic. My left is held high while my right is frozen in the air, ready to attack the last remains of my rice bowl waiting patiently below. I’m a wild madman conducting a renegade orchestra, out of tune and in need of some water. It is time to let it rest. The Chinese woman rises, wobbles slightly, and then limps away.

“Where are you going?”

“I have to pee.”

And so I put down my chopsticks and rise as well. I’m about to return to the living room for more of Bolaño’s Last Evenings on Earth, but on second thought, as the good foot soldier in the war on dirty dishing, I instead gather empty plates and bowls from our table and place them in the sink. Yes, what I meant to say is that I’m a future father, practical, mild-mannered, and prepared to clean and rinse.