There is an idea, popular in neo-Nazi circles, that Jews intend to lower the white birth rate by promoting debauchery. Feminism and free love. Abortion and homosexuality. Drugs and internet porn. All of these, in the white supremacist mind, are ruses to divert the Aryan race from procreation. Some neo-Nazis even claim that cats are “purring Jews,” insidiously evolved to occupy white women’s motherly instincts which would otherwise go towards raising human litters.

One flaw strikes us immediately about this belief. If international Jewry had a hostile plan to outbreed white Gentiles, we might expect the Jewish birth rate to be burgeoning. Yet outside of Israel it is not, and on the whole secular liberal Jews are hardly more fecund than secular liberal Anglo-Saxons. Indeed, many seem just as ensnared in gayness, kink and cat-love as their supposed targets. Herein lies the paradox. The surest way to encourage decadence is to lead by example, but this means the Pied Piper must become decadent too.

What have white supremacists done to address this contradiction? For the most part, nothing. But the book I am about to describe is a new and intriguing exception.

The Crèche-City of Tel Poriyut: A Personal Account was released in late 2016 by Savitri Press, a far-right esoteric publisher based in Wilmington, Delaware. Its authorship is anonymous. A note by the acquiring editor informs us that the author (who wrote under the pseudonym “T.W. Duke”) died several months before publication and insisted that the work should only be made available posthumously. The note concludes:

It was the late author's wish not to be mentioned by name anywhere within this text. The facts of his autobiography suggest that he was a very famous person with good reason to be cautious. His manuscript reached us in November 2015, in a parcel with no return address. It was accompanied by a letter claiming that "Mr. Duke" was in the end stages of an unnamed terminal illness. We were ready to treat the letter as a hoax, until the following year saw the unexpected death of a celebrity whose life details were a close match for our author's. We would love to believe that "Mr. Duke" was that celebrity, though the discretion he took in reaching us makes it difficult to confirm his identity. And given the explosive claims made in his memoir, his discretion is wholly warranted.

Finally, we must emphasize that the author's conclusions about the Holocaust are not necessarily those of Savitri Press.

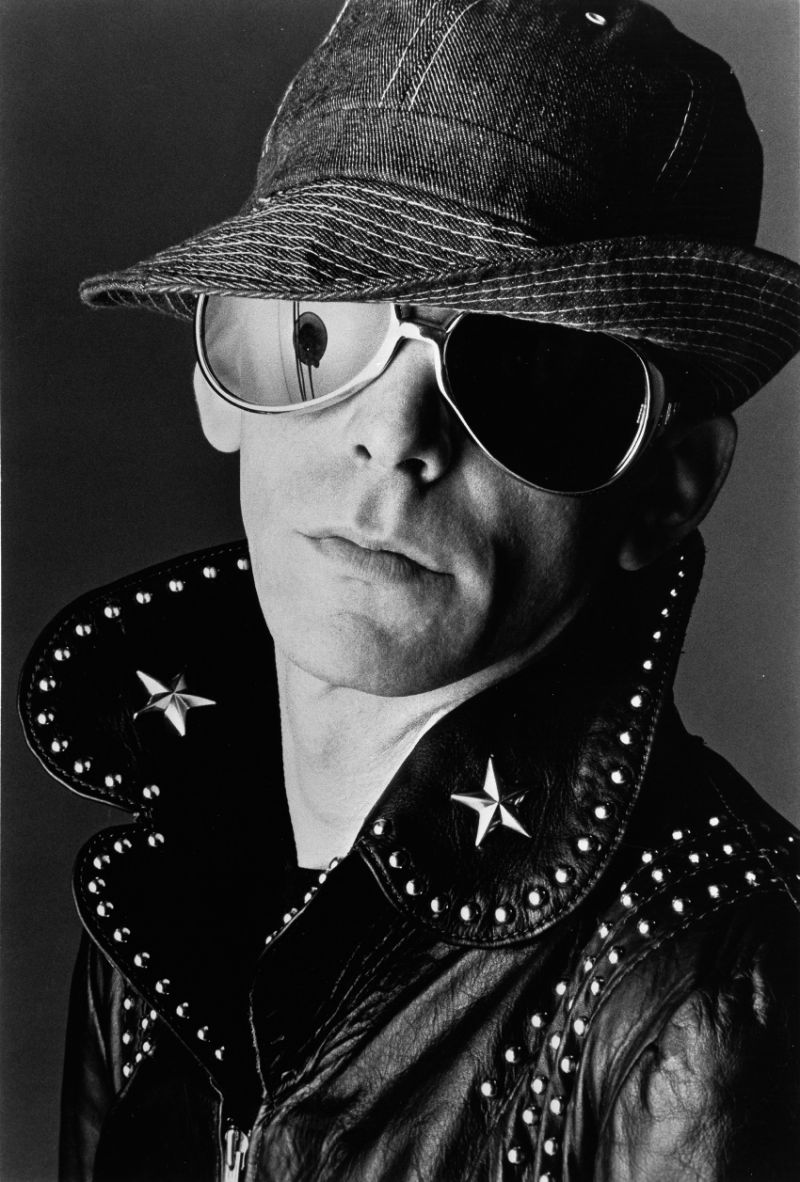

Mr. Duke does not have the background we would imagine for someone published by a neo-Nazi press. By his own account, he was a British rock musician famed for his androgyny and for a bewildering flurry of stage personas he adopted and discarded throughout the 1970s. He led a life of hedonism, fueled by cocaine and bisexual trysts, and showed no interest in “the welfare of the white race or the Jewish agenda” until (in his own words) “certain accidental events forced me wide awake.” The catalyst for those events was his friendship with Lou Reed.

Mr. Duke first met Reed when the American singer stayed in London in 1972. The two became fast friends and Mr. Duke even produced one of Reed’s solo albums. Reed already had a minor reputation as an enfant terrible, an omnisexual, cross-dressing drug fiend whose music was labelled “gutter rock” by tabloid journalists. The critic Lester Bangs would go on to characterize him as “a completely depraved pervert and pathetic death dwarf.” But these slurs pale in comparison to Mr. Duke’s memory of his early contact with Reed. The “Lou” he recalls was a monstrous character who boasted of sexual misadventures with dogs, sows, children and corpses; who had such a tolerance to drugs that he could wolf down whole packets of Quaaludes without showing a hint of sedation (indeed, he delighted in drinking from the same magnums of champagne that he had spiked to subdue his “groupies”); who rolled up glossy magazines, lit them like cigars and burned himself without flinching; who had no fear of tetanus, gangrene, endocarditis or chlamydia; who molested grandmothers on double-decker buses, shared rusty needles with homeless strangers, and (if some of his braggadocio was worth believing) may even have been a serial killer in his native New York. Against this litany of crimes, it seems almost trivial that Reed was Jewish. Nevertheless, Mr. Duke would find the fact increasingly important.

“At that stage in my life, I was jaded enough that Lou’s psychopathy didn’t bother me,” Mr. Duke writes, “but I had to draw the line when his dope habit interfered with recording.” During one studio session, Reed fell asleep in the middle of a song, stumbled over a microphone stand and suffered a gash to his chin. Mr. Duke decided that the New Yorker was in no condition to record and gave him a fortnight to “dry out.” He left Reed to languish in his hotel room with a supply of mineral water, rehydration salts, adult diapers, Marmite, and diet biscuits.

Three days later, when he imagined Reed was at the height of his withdrawal agonies, Mr. Duke took a stroll around Piccadilly Circus. There, at the corner of Shaftesbury Avenue, he saw something that made him freeze. A primly dressed Jewish family was standing outside the London Pavilion. By their cameras and bags of souvenirs, Mr. Duke judged them to be tourists. The mother was wearing a “bandanna-like scarf on her head” while “minding three boys in white yarmulkes and their two sisters.” The father, clean-shaven in a three-piece suit, looked identical to Lou Reed.

Mr. Duke stared at the man in astonishment: “I could never imagine Lou raising a family, let alone the happy, perky Brady Bunch gaggle in front of me. They looked like the sort of people who said grace before meals!” The father seemed “as fresh and sober and healthy as a newborn babe,” yet his face was “the spitting image of Lou’s.” He even had a Band-Aid on his chin.

When he noticed Mr. Duke watching him and his family, he reacted angrily: “What are you staring at, daffodil? Take a hike, you pansy freak!” Apparently ill at ease with long-haired, elfin musicians, the mother ordered the boys to look away and covered her daughters’ eyes. Before Mr. Duke could ask the man what had happened to his chin, he hailed a black limousine that had been driving in circles amongst the Piccadilly traffic and the family fled into the car. Mr. Duke ran straight to Reed’s hotel room and found the New Yorker sweating and trembling just as expected. Reed denied any knowledge of the upright Jewish family that Mr. Duke had seen. To him it sounded like a bad joke. He changed the topic to Valium and asked Mr. Duke whether he was “holding” any.

Mr. Duke continued to ponder the meaning of that event: “Could Lou be leading a double life, like the Scarlet Pimpernel of yore? Did he have a twin brother? Was it a random coincidence?” For years, he found no answer to these questions.

By 1975, Mr. Duke had moved to Los Angeles, where he had been cast in a film about “a dejected but superior being.” (His memoir blurs many details for the sake of anonymity.) He was lazing in his Bel-Air villa one August afternoon and waiting for his physician, Dr. Schnoebelen, whose practice thrived on handling the “special demands” of A-list patients. From the doctor, he expected to receive a script for “250 tablets of Dilaudid and some reds, plus enough Biphetamine to make a plague of locusts lose its appetite.” The doorbell chimed. Instead of Dr. Schnoebelen, he found an anxious-eyed Reed wearing a soiled bomber jacket and clutching an overnight bag. Reed asked him for a favor. He wanted to stay with Mr. Duke for two months and wean himself from heroin. It was important that he did this in total secrecy. Mr. Duke was not to tell anyone that Reed was his guest or that he was recovering from drug problems. Could this be arranged?

Mr. Duke was about to voice his doubts about the plan (for his home was “not the best place to seek respite from narcotics”) when the doorbell chimed again.

“That would be Dr. Schnoebelen.”

“Oh shit! Don’t say a peep about this to him!” Reed hissed, and scurried to hide in the laundry.

After the doctor left, Reed continued to be evasive about his reasons for choosing Mr. Duke’s house to recuperate incognito. Reluctantly, Mr. Duke granted his wish. He installed Reed at the far end of the villa’s east wing, in a secluded guest room with its own bar and Jacuzzi. Reed insisted on being chained by the ankle to one of the fixed barstools. His twenty-six-foot chain was long enough for him to reach the en suite bathroom and his waterbed; it kept him, however, from escaping the house and rekindling old acquaintances with dealers. For the first six weeks, Mr. Duke issued him with Dilaudid, tapering down the dose to a quarter-tablet nocte. In late September, he began to withdraw cold turkey. These were not the withdrawal symptoms Mr. Duke had seen in London. Now Reed looked “clammy, febrile and hideously pallid,” as if he were “only a heartbeat away from going into shock.” Still, he refused Mr. Duke’s offers to get medical attention.

As the week of agony drew to a close, a look of unexpected gratitude appeared on his face and, shivering in the hot Jacuzzi, he finally divulged his secret. He had indeed been in Piccadilly Circus when Mr. Duke saw him, and the tale behind his double life was more world-shaking than anything his friend had imagined.

For centuries (Reed explained) the Jewish people had been perfectly innocent of the crimes malicious Gentiles charged them with. They didn’t poison wells or make matzo from the blood of Christian babes or conspire to rule the world. Naively, they hoped to live in peace with the Gentiles who outnumbered and slandered them. The Holocaust shattered that innocence. In 1946, a vast assembly of Jewish leaders met in London for confidential talks on how to prevent such a catastrophe from happening again. Various flimsy schemes floated around the chamber until a delegate from Portugal broke through the indecision. The answer was obvious, he said, so obvious that generations of daft anti-Semites had already produced it: why not form an international conspiracy? So far, Jews hadn’t fared well by being disorganized. The Gentile nations had proven themselves reckless, irrational and—if left unchecked—capable of the most horrific genocide. They had to be attenuated for their own good. (“I’m sorry if that sounds patronizing,” Reed interjected.) The assembly settled on a cautious plan. It would not work to use violence or cruelty in such circumstances. Sterilization was too sinister, too much like the methods of the Nazis, and could backfire dreadfully if discovered. It was better to soften the Gentiles culturally and morally, and with their full consent. A vanguard of “Judas goats” would promote a culture of hedonism, a sexual revolution to sweep away marriage, family stability and procreation. As a result, the Gentile world would be too atomized and dissolute to devote itself to persecuting Jews. If the Western birth rate waned enough, there might one day be as many Jews as Gentiles, and Jewish communities would be able to defend themselves with ease. Since then, countless Zionist field agents embedded in Western society had worked tirelessly to cultivate vice among the masses. Reed was one of them.

Naturally, it was counterproductive for the agents themselves to become debauched and childless. They still had a duty to bring Jewish babies into the world: “One for mother, one for father, three for Zion!” But how could anyone focus on debauching goyim when they had kids to look after? Foreseeing this problem, the assembly had ordered the construction of a hidden “crèche-city” in the heart of Paraguay. Its name was Tel Poriyut and it served as a refuge where Zionist agents could deposit their offspring while they masqueraded as sybarites. Those had been Reed’s children Mr. Duke saw in London, on one of their annual excursions to the Gentile world. And Reed wasn’t the only one with a hidden family. That poet of pederasty, Allen Ginsberg, had quietly fathered four sons and three daughters. In Tel Poriyut (which Reed now said was in the Amazon jungle), Ginsberg was firmly heterosexual and revered as a manly patriot. The pornographers Radley Metzger and Al Goldstein, the adult actor Herschel Savage, the lesbian separatist Andrea Dworkin—all of them led secretly wholesome lives behind Gentile society’s back. Agent couples followed a rotating schedule. Sometimes it was the father’s turn to mind the children while the mother was out corrupting the Gentile world. Then the two would exchange roles.

Tel Poriyut (Reed had shifted its location to outback Australia) was a wonderful place to grow up. Its houses were built in the same neo-Egyptian style as the handsomest synagogues of the nineteenth century. Every child learned at least six languages and had weekly computer lessons—a princely rarity in 1975. In their free time, children could join chess clubs, barbershop quartets, debate societies, football teams, fencing clubs, book clubs, croquet clubs, horse-riding groups and the Tel Poriyut Youth Orchestra. There was a picture theatre in the city that screened Shirley Temple musicals and Jerry Lewis comedies. If the children yearned for the outdoors, they could go hiking in the mountains of New Zealand (which now, according to Reed, enclosed the city at all sides). Once or twice a year, the children had holidays in the Gentile world, travelling on fake passports so that outsiders would never guess Zion’s true population. Once they reached maturity, some would get permanent identities as citizens of Gentile nations and continue their parents’ work. Others would stay in Tel Poriyut to keep the crèche-city running. The system worked brilliantly. While Gentile children grew up wounded by divorce, abuse, neglect and family breakdown, Tel Poriyut made sure that all of its children were raised with love. They developed healthy attachments and solid values. In the city’s twenty-five years of existence, no youth had ever shown signs of the character pathology so wretchedly common in the outside world. Reed mentioned this with pride, even as his spindly body trembled for need of opioids.

Reed’s children, of course, knew nothing of his rock career, of his songs about drugs, delinquency and sadomasochism. They saw their father only as a hero fighting for the Jewish people’s survival. How could a ten-year-old understand that the salvation of one world meant the perversion of another? That was why Reed had acted so coldly when Mr. Duke collided with his “precious family time.” But operating in deep cover as a junkie had taken its toll on Reed. His addiction was no longer a sham. In such a state, he couldn’t face returning to his family. He’d needed a secret place to “get straight again,” away from the eyes of his fellow Zionists. Truly, Mr. Duke had saved his skin!

Ten days later, Reed announced that he was fit enough to leave for Tel Poriyut (whose position, he suddenly insisted, was in Patagonia). He thanked Mr. Duke once more and cautioned him to stay silent about what he’d learned.

With Reed out of the house, Mr. Duke’s first reaction was anger and disgust: “I felt sick at the ruse that had been perpetuated on me and the whole European race. I was ashamed that I’d wasted my life on cocaine and shallow bisexual flings instead of fatherhood and personal virtue.” His next album would be infamous for its flirtation with fascist imagery and puzzling allusions to the Kabbalah. Upon its release, Mr. Duke was visited by “a very stern and sober Lou” who warned him that the Zionist network would “not be amused” if he continued in this fashion. “You’re lucky: they think it’s just the coke,” Reed told him.

Mr. Duke relented, but “a burning private curiosity” drove him to search for Tel Poriyut during the late 1970s and early 80s. Being an erratic rock star gave him the freedom to take unusual hiatuses without arousing suspicion. His managers assumed that he was using the privacy to work on new material and never dared to interrupt his periods of self-exile. Without informing even his closest friends, he made a series of one-man expeditions to remote areas across the globe. His account of these journeys is perhaps the most remarkable part of his memoir. Several chapters contain such excellent travel writing that the reader can almost forget Mr. Duke’s politics and bask in his descriptions of sublime but unforgiving landscapes and the ingenuity with which he navigated and endured them. If these chapters have any basis in reality, it means that Mr. Duke was not only an influential rock musician but also heir to a tradition of great British explorers such as Richard Francis Burton and Apsley Cherry-Garrard.

His search for Tel Poriyut was relentless. One adventure brought him to Western Australia, where he bought a Jeep and drove through the Great Victoria Desert. After running out of beef jerky and potable water, he hunted feral camels and drank their blood to stay hydrated. Crossing the Southern Alps of New Zealand, he nearly died after a flock of carnivorous kea parrots stole his food rations and damaged his camping equipment. To survive, he set traps for the keas, ate their flesh and stuffed his jacket with their feathers. In Patagonia, he climbed the jagged cliffs of Cerro Torre. There, a ruptured appendix forced him to perform surgery on himself using a utility knife. Posing as a German filmmaker named “Siegfried Sternenstaub,” he travelled to Brazil and hoped to hire a riverboat to carry him along the Amazon, but abandoned the mission when the paparazzi ambushed him in Rio. Several expeditions brought him close to death. More than once, he returned to civilization looking “grizzled, malnourished, hirsute and battered by the elements.” But his contacts in the recording industry were left none the wiser. They put his appearance down to drug abuse, disordered eating or simply the mental toll of prolonged solitude. At a party, Brian Eno told him, “I think you’re working too hard.” And for all his efforts, he hadn’t found Tel Poriyut.

Mr. Duke attempted his last expedition in July 1982. Through “a close reading of geography imbued by the Kabbalah,” he theorized that the crèche-city’s true location was North Sentinel Island in the Bay of Bengal. He’d read a National Geographic article which claimed that the Sentinelese islanders were one of the world’s last uncontacted tribes and violently repelled all outside visitors. But the article’s author had a Jewish name. This made Mr. Duke suspect that the islanders were a fabrication, a savage facade to camouflage the most sophisticated city ever built. For his mission to penetrate that facade, he decided at last to recruit a band of accomplices. At that time, Britain had a nascent subculture of “white power music” growing from the Rock Against Communism concerts frequented by far-right punks and skinheads. Discretely—and aware of the risk to his reputation—Mr. Duke approached members of that scene. He offered them generous sums of money if they would join him on a quest to expose a secret Jewish city. Despite the oddity of the proposal, Mr. Duke’s celebrity appeal won five skinheads to his cause. For caution’s sake, he asked each accomplice to make his own separate journey to Phuket. There, on Thailand’s western coast, the expedition party came together and hired a boat.

They sailed off before dawn into the Andaman Sea. Close to midday, one skinhead became ill, perhaps due to ciguatera poisoning from a fish he had caught and eaten for breakfast. Reporting that his face and toes felt numb, he soon collapsed into a coma and died of respiratory paralysis. Mr. Duke allowed the crew to give their friend a burial at sea according to Norse pagan custom. Uttering a prayer to Odin, they loaded his body into a spare wooden rowboat, set it on fire with kerosene, and cast it adrift. Mr. Duke was undaunted and pressed them to sail on for the island. To avoid detection by the Indian Coast Guard, they took a circuitous route through dangerous stretches of shallow water studded with coral reefs and limestone pillars. After colliding with jetsam—in the form of a turboprop engine from some long-forgotten air disaster—their boat began taking on water. The group escaped in an inflatable raft. Even then, Mr. Duke refused to sail back to civilization and, pointing a harpoon gun at his men, forced them to set course for North Sentinel Island.

Three hours later, they arrived at the island shore. Immediately, a dozen islanders surrounded them and another skinhead was killed by a hail of arrows to the neck. Mr. Duke and his three surviving companions were taken to a village of crude huts and imprisoned in earthen pits. Still convinced that the natives were “Jewish actors,” Mr. Duke tried to bargain with them in English and snippets of beginner’s Hebrew. To his dismay, the natives understood nothing. They removed one skinhead from his pit and slaughtered him. Mr. Duke half-expected them to be cannibals, but instead of eating their victim, they roasted his limbs as an offering to a deity of some kind. As they did this, a village elder removed the skinhead’s thyroid gland and inspected it. He seemed to disapprove of its quality and gestured for another victim. The Sentinelese grabbed Mr. Duke, who feared his life was over. But the ritual was interrupted by the rattle of a helicopter. The sound of three-round bursts cracked through the air and the natives “scattered like pigeons” when they heard the covering fire. Peering up, Mr. Duke saw Lou Reed seated inside the helicopter with a team of “what appeared to be Israeli commandos wearing unmarked uniforms.”

Mr. Duke was airlifted from the village, though Reed chose to leave the skinheads behind at the natives’ mercy. On their ride back to Thailand, Reed informed Mr. Duke that he hadn’t been as discrete as he’d thought. Zionist agents had tailed him constantly during his secret quests. Reed had “jumped through hoops you wouldn’t believe” to persuade his superiors not to have Mr. Duke assassinated. This was his final warning to behave.

As they conversed, Mr. Duke noticed something new in his friend’s demeanor. The New Yorker looked somber and weary. He lamented that the Zionist plan had been stricken by “complications.” A previously unknown virus, transmitted by bodily fluids, was spreading throughout the globe. Its symptoms were so gruesome that Reed feared it could undo thirty years of transgression overnight. Family values threatened to return and perhaps even gays would shrink away from libertinage. The whole conspiracy was in crisis.

Reed felt the need to speak of happier things. He showed Mr. Duke a photograph of his youngest son, Nahum, who was “growing into a fine boy.” At twelve, he already spoke French and Russian fluently and knew more Hebrew than his father. He would badger his rabbis with “fucking hard questions” about ethics, metaphysics, and scripture. The boy also played the piano and hoped to become “a heart surgeon or an ornithologist” when he grew up. There was joy in Reed’s voice, “as if fathering Nahum was an accomplishment in itself, global conspiracies be damned.” The sight of such tenderness, such parental affection, left Mr. Duke deeply moved. “I had a sudden twinge of guilt,” he writes. “I felt ashamed for trying to intrude on the privacy of that love, and so many loves like it, which deserved to be left in peace and happiness. It was seeing Lou’s love for Nahum, and not any warnings about my safety, that finally assured my silence and made me quit nosing into the mystery of Tel Poriyut.”

Reed and Mr. Duke never discussed Tel Poriyut again for the rest of their lives. Whenever Mr. Duke alluded to it, Reed feigned perfect ignorance and held up his front as an ageing libertine. But, even after relinquishing his quest, Mr. Duke continued to speculate about the whereabouts of the crèche-city: “My ultimate theory is that Tel Poriyut exists somewhere in Antarctica, but it’s too late for me to hunt for it now. Too late to be hateful. I’m nearly seventy—and nearly dead. Perhaps you, Reader, can prove me right or wrong.”

We cannot escape the overwhelming likelihood that Mr. Duke’s “memoir” is a forgery, like the Protocols of Zion before it. Unlike that despicable pamphlet, however, it at least bears no marks of plagiarism. If it is false, the falsehood is entirely original. What could have motivated its author (who, in contrast to his persona of Mr. Duke, might still be drawing breath even now) to write such a tale? While its narrative would appear to seal a gaping hole in the neo-Nazi version of events, it opens other holes in the process. At no point in the book does Mr. Duke object to the reality of the Holocaust, a view which has caused his publisher some discomfort. And, compared to other anti-Semitic texts, The Crèche-City of Tel Poriyut is not very effective at making Jews into an object of hatred. Perhaps an urge for mischief guided the author’s hand. If not, we can only assume that his goal was to redeem Lou Reed.