Storms in the U.S. are very likely to hit Britain a few days later. Political storms take a bit longer, but their arrival is almost as certain. In both cases, however, their effects may be markedly different. The U.K. election at the end of 2019, which vindicated a then tottering Conservative government and installed Boris Johnson for five years with a very comfortable overall majority of 80 in a House of Commons of 630, is a case in point.

"Liberal rationalism is, at least at the moment, an electoral dog: the quickest way to annoy or bore an English middle-class or working-class voter is to talk political theory or to lecture him on questions of political principle."

In many ways 2019 in the U.K. has a good deal in common with the U.S. Presidential Election of 2016. For one thing, it was remarkably presidential, in a way that few elections in the U.K. are. Very large numbers of people didn’t vote for Tory ideology, but rather for Boris and his way of doing politics (more on this later). For another, to a significant extent it was lost by the defeated party rather than won by the winner. Indeed, what can be described as the unique non-selling-point was similar in both cases. Both Hillary in 2016 and Jeremy Corbyn, Boris Johnson’s Labour opponent in 2019, simply failed to take notice of what electors wanted: Hillary seemed to regard herself as the Democratic heiress entitled to inherit the votes of women, minorities, and Obama’s supporters without bothering to tell them why they should vote for her, while Corbyn was more concerned with keeping up what he saw as the true socialist and internationalist faith than with seriously persuading unbelievers to follow him into the promised land. Both rightly repelled electors resentful of being regarded as pawns in someone else’s game.

But there the parallel ends. Trump won in 2016, and in every likelihood will win this year, as an iconoclast and anti-politician, rather than on the basis of any particular liking for him or his friends. Johnson is different. Closer in political temperament to Reagan than Trump, he very deliberately gives the impression of the nice guy with guts who sets out a small number of clear objectives and then, in an endearingly bumbling way, does his best to achieve them. In 2019 the objectives laid out by Johnson were essentially two. One you can guess: the final, definitive extrication of the U.K from the European Union and an end to the dithering that had infuriated and exasperated large sections of the U.K. electorate since 2016. The other objective attracted less publicity across the Atlantic, but was equally important to the voters. Johnson went out of his way to emphasize that his concern was to improve the economy and build up the infrastructure of provincial Britain, including the British equivalents of places such as Flint, Michigan or Scranton, Pennsylvania (of which there are an uncomfortable number, for example the erstwhile coal and steel towns of Wrexham and Middlesbrough). It was voters in those places, many of which hadn’t returned a Tory Member of Parliament for sixty years or more, who gave him his majority.

And that brings us to a much more important point, and one genuinely unique to Britain. It is highly arguable that this election result has quietly turned much of the British politics of the last hundred years on its head. To be sure, this is a big claim, but it has sound reasoning behind it.

Articulate opponents of the new Johnson government—well-heeled, expensively-educated liberal brahmins in management, the media, and the civil service who cannot stomach Brexit and mourn the abrupt end to their hegemony which had lasted since the 1950s—refer to it as a far-right authoritarian aberration, a coup by the old upper class, and a reactionary throw-back towards a vanished world. On the first two points they are comically wrong: Johnson is socially liberal and fiscally relaxed, and his new intake, especially in ex-Labour seats, almost entirely without any social pretension whatever. On the third, by contrast, they are absolutely right. This victorious Conservative Party is indeed a throw-back, although not the kind they think. Forget Mrs. Thatcher and the slightly silly free-market ideologues of the roaring 1980s; forget even the buttoned-up and repressive “you never had it so good, so let business get on with it” 1950s of Harold Macmillan. Johnson’s party since 2019 actually resembles something much older: namely, the remodeled Conservative Party associated with Benjamin Disraeli in the 1860s and Lord Salisbury in the 1880s. Light on dogma and ideology, this party rejected the nineteenth-century liberal idea that the human race was perfectible if only it was administered on rational grounds with outdated baggage cleared away; instead, it preferred to take note of the institutions of English society, to support them, and to build on them. It was the Conservative Party that gave Britain such things as the Second Reform Act extending the franchise in 1867 and, in the 1880s, a pioneering line of factory legislation improving the lot of both young and female workers.

True, this flowering of true conservative thought was quickly obscured. The conservatives in the twentieth century followed the siren calls of rationalism previously associated with nineteenth-century liberals, allowing themselves to become, in increasingly dreary succession, supporters of business, laissez-faire, monetarism, old-fashioned moral values, and the supposed magic of free markets. For that matter, under David Cameron the party became almost Labour-lite when it took on an attachment to egalitarianism and social liberalism. The phrase “one-nation Toryism,” which to Disraeli had meant government pragmatically doing the best it could for all classes, and preserving harmonious relations between them by righting obvious injustices, had morphed by the 1980s into essentially a call by a leftish sect within the party for the Conservatives to ape Labour by adopting a slightly less extreme version of socialism. No wonder that, under prime ministers such as Theresa May, thinking people found it difficult to see any respectable reason to vote Tory.

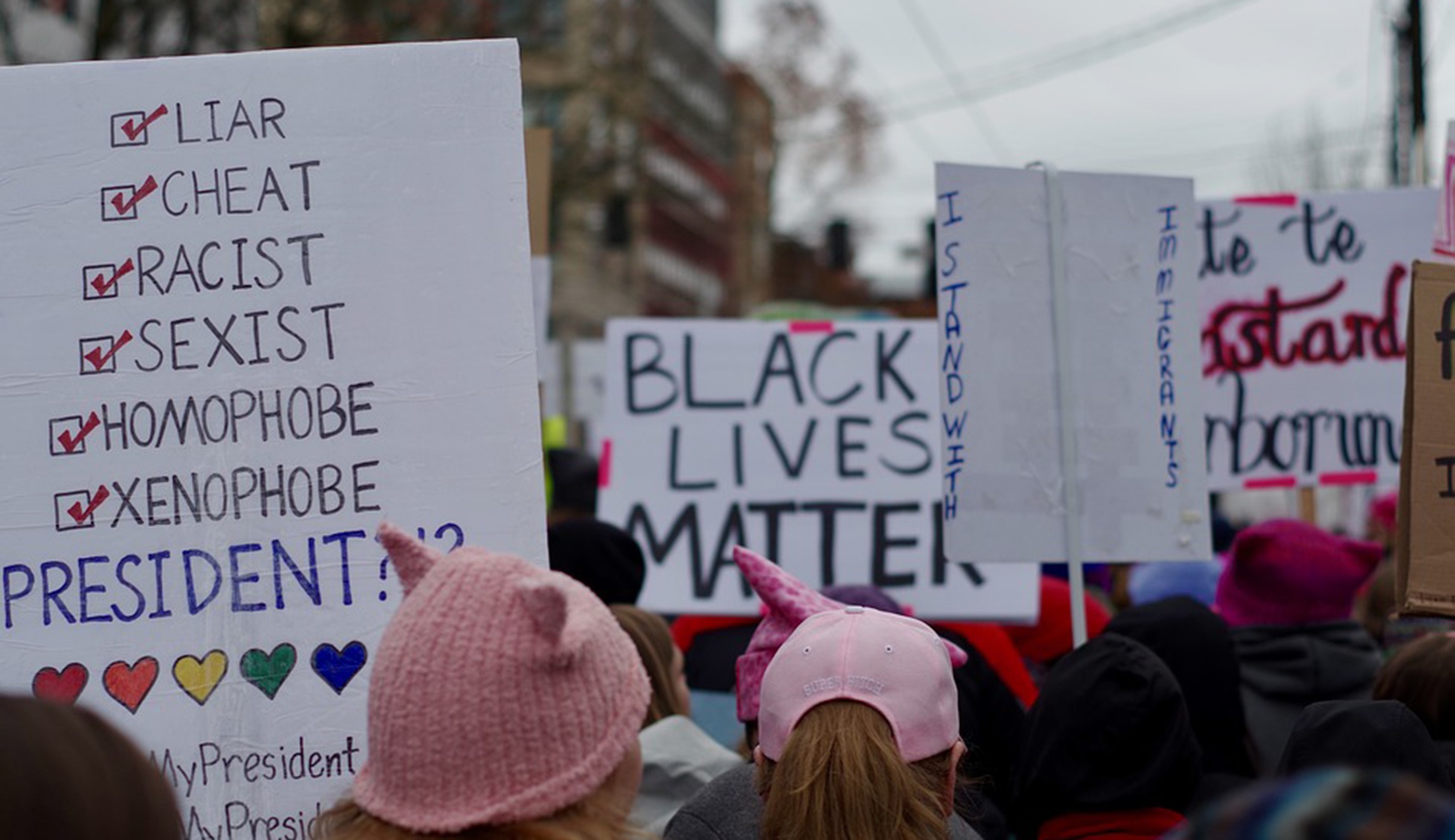

The only reason the Conservatives survived as more than a fringe group was that the opposition Labour Party was in even worse shape. Tony Blair’s very middle-class victory in 1997 had been exhilarating at the time, but was ultimately disastrous in removing any serious connection between Labour and, well, labor. By 2010 his party had become a cosmopolitan, self-obsessed middle-class club. Beguiled by the idea of the E.U. and openly contemptuous of the idea of the nation state, its ruling elite relied on a working class whose values it increasingly despised to continue to vote for it out of some kind of family loyalty. Furthermore, in a vain effort to attract minorities, the Labour Party, like its lefty brethren across the Atlantic, desperately attempted to make up for any losses by adoption of a curious, and rather unattractive, mélange of wokeness and identity politics.

It was this folly that provided Johnson’s opportunity to break with the twentieth century and to remake the Conservative Party on nineteenth century lines. In the last ten years some sharp Tory advisers had noticed a vital demographic point and—unlike the advisers of the Labour and Liberal Democrat parties, who also knew it but preferred to do nothing—acted on it. They saw that a working class which had once atavistically voted Labour, on the vaguely comforting basis that providers of labor should somehow dictate how its products were distributed, had almost entirely vanished.

The new working class was different. Uninterested in deep political theory about the value of labor and merely wanting to get on in life, they actually had rather simple and old-fashioned social views. These included a patriotic pride in being British and a desire to control their national destiny; a feeling that government obviously had to look after those who couldn’t cope and do it efficiently; a dislike of being pontificated to; and a large dislike of the paraphernalia of woke identity politics. They might not care for traditional conservative ideology, but they were there for the taking by any party that was prepared to speak to them in their own terms. There was, in other words, ample space for a bomb to be placed under the old politics that would blow it to smithereens.

This is just what happened. The fuse was actually lit not by the Conservatives, but by a much smaller party, that is, the single-issue Brexit Party, whose sole aim was to ensure the U.K. left the E.U. as decisively as possible. In 2019, two and a half years after voting to leave the E.U. but not yet having left it, Britain had to hold understandably unpopular elections to the European Parliament. The Brexit Party, playing to the instincts just mentioned, cleaned up. And yet, the opposition parties still chose not to see that their own different form of politics—intellectual, rationalistic, de haut en bas—was on the way out. This failure left the goal open to Boris Johnson’s Conservatives in the 2019 election, and the rest is history.

What now? We know two things. One is that we are back to something like nineteenth-century politics. With political pragmatism once more pitted against dry rationalism, there are wide opportunities for any party prepared to abandon intellectual gymnastics and ideological argument, to listen carefully to what communities want and give it to them. Secondly, we are at a point on the political spectrum where electioneering of this kind is in the ascendant. Liberal rationalism is, at least at the moment, an electoral dog: the quickest way to annoy or bore an English middle-class or working-class voter is to talk political theory or to lecture him on questions of political principle.

Certainly, this election was momentous not only for Britain and the Conservative Party, but for all parties and the entire U.K. political establishment. If Labour and Liberal Democrats (the smaller opposition party, who were also hammered in 2019) want to recover anytime soon from their trouncing by Johnson, they must change fast. Surely they do not want to bet on the British people suddenly regaining a taste for high-flown political argument, because that seems very unlikely in the foreseeable future. Labour and Liberal Democrats will have to be much more prepared to go against all the instincts of their educated comfortable middle-class membership and abandon a great deal of intellectual baggage. The Labour Party must, for instance, get rid of its high-minded internationalism, its overt multiculturalism, and its open mistrust of the idea of Britishness. The Liberal Democrats’ fascination with electoral systems and its quasi-religious attachment to the idea of the E.U. are equally electoral albatrosses.

Both parties will also have to do something drastic about the zealots who in the last ten years have succeeded in inserting into leftish politics dubious claims concerning Muslim, female, gay, or trans oppression. For though such phenomena may make a party attractive to intellectuals, they are toxic to most people. It remains to be seen whether either or both of the opposition parties will succeed. They face the problem that party members, unlike the voters they need, are overwhelmingly either starry-eyed students mesmerized by all these new woke ideas or educated middle-class liberals.

Still, this is not impossible to overcome for someone with a suitable amount of guile. If they fail, one thing is sure: a new party, or a splinter from an old one, will arise to combat Johnson. One has to remember, after all, that two can play the game of listening carefully to people and giving them what they want. The Conservatives have no monopoly here, and indeed, intelligent Labour-leaning commentators are already saying that the best chance for a challenge to Johnson in the medium term is a socially conservative, communitarian party with a serious high-tax-high-spend policy. No matter what happens, one thing is clear: the old-style parties, on whatever side, are fast becoming an irrelevance.

Keen readers probably will have noticed that so far I have concentrated almost entirely on England, where most of the battles were fought. What about the other parts of the U.K., Scotland and Northern Ireland? These raise more complex issues, especially since politics in Northern Ireland has to reckon with an additional deep religious split not seen anywhere else in the U.K. But to some extent similar arguments may apply here too, at least in Northern Ireland. There voting now splits not so much on the basis of political philosophy as on the basis of a different kind of patriotism, with Unionists showing pride in being British and nationalists preferring to stress their Irish nationality. That aside, however, much of the rest of Northern Ireland politics has for a long time been community-based rather than ideological. One might even say that in this respect Northern Ireland reached the position obtaining in England some time ago.

Scotland is less straightforward. There, uniquely in the U.K., Johnson was overwhelmingly rejected in 2019. Instead the voting went overwhelmingly in favor of a nationalist grouping, the Scottish National Party. Now, to some extent a variant form of patriotism is at work here too, albeit to a very different effect. Scots tend to regard themselves as Scottish first and British second; and this preference clearly chimes with the stated aims of the Nationalists, whose raison d’être is to express a strong sense of political grievance against rule from London and ultimately call for independence. But apart from this, Scotland may be the exception to the suggestion in this article. The voting here was, it has to be said, more ideological. For one thing, Scots have a strong emotional attachment to the rationalist project of the E.U., a view undoubtedly shared and exploited by the Nationalists.

Furthermore, under the separatist surface (which one suspects a number of Scottish electors do not take seriously), many of the Nationalists’ policies were not that different from the Labour Party south of the border; tax-and-spend socialist, socially rather dirigiste, and where necessary tinged with some identity politics. This is perhaps not surprising, given that until 2015 Scotland was largely Labour, from whose indolent hands it was then wrested by the Nationalists in that year. Essentially it seems that the previous atavistic habits of voting Labour have simply been transferred lock, stock and barrel to the usurpers. If this is right, then at least for the moment Scotland may be the exception to the transformation of U.K. politics. Whether the Scots will later fall into line, or whether they will continue cussedly different from the English in politics as in many other things, we will have to wait and see.