It is 1919, A middle-aged man looks upon his infant daughter in his cradle, while a terrible storm rages from the Atlantic to the west, its “roof-leveling wind” broken only by “Gregory’s wood and one bare hill.” He has walked and prayed for an hour, he says, “because of the great gloom that is in my mind.”

“This hiddenness, Yeats tells us, is not a trivial thing. It bespeaks greatness of soul.”

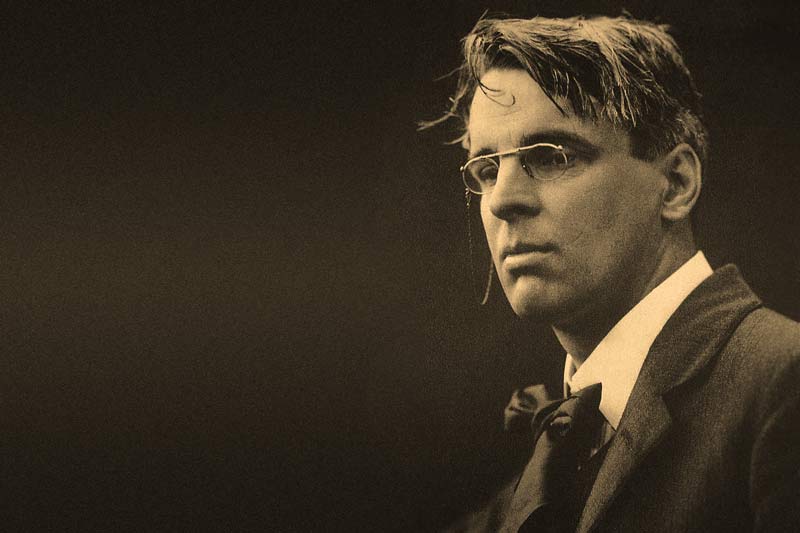

I suppose if we gave students to read “A Prayer for My Daughter,” by that flawless crafter of verse, William Butler Yeats, we might appeal to his staunch Irish patriotism, hurling itself against the injustice of British rule and the fanaticism of many of the rebels. We might also attribute to sour grapes his bitter allusion to Maud Gonne, who had rejected his last proposal of marriage three years before:

Have I not seen the loveliest woman born

Out of the mouth of Plenty’s horn,

Because of her opinionated mind

Barter that horn and every good

By quiet natures understood

For an oldbellows full of angry wind?

Anything, anything, rather than take seriously the prayer itself, which is that his daughter will be genuinely happy in life, making others around her happy, by being a woman in a woman’s private sphere, and by accepting that horn of plenty, whose good things the world of politics can only intrude upon to spoil.

“Her voice was ever sweet,” says Lear, holding the body of his daughter Cordelia in his arms, “Gentle and low, an excellent thing in woman,” not like the vocal fry we hear in the snappish Goneril, or the aggressive ambition we hear in Regan, ever interrupting her equally wicked husband. I doubt there is a man alive, whatever his politics may be, who can say honestly that he thrills to hear the shriek and shrill of a political woman. His response is neurological, we might say. Maybe so, but let us not evade the point, which is that he hears it as wrong, a denial or a spoiling of something good. What is that good? The poet tells us:

May she become a flourishing hidden tree

That all her thoughts may like the linnet be,

And have no business but dispensing round

Their magnanimities of sound,

Nor but in merriment begin a chase,

Nor but in merriment a quarrel.

O may she live like some green laurel

Rooted in one dear perpetual place.

It is life, the heart of life. People who say they love nature, saying it from the safe space of an airport terminal, sending a social media message about the precious jungles of the Amazon, will not see the nature before their eyes, in man and woman, and will not see that the private world of woman is to the political world of man as the Lake Isle of Innisfree, for Yeats, was to the “pavements gray” of the city. You can’t grow a laurel tree in pavement. The laurel—sacred to poets, and ever green—flourishes because it is hidden, as the small linnet sings his heart out from the coverts of its branches. This hiddenness, Yeats tells us, is not a trivial thing. It bespeaks greatness of soul. The woman knows and dwells in a merriment that has all but vanished from our hard-edged, grim, touchy, vindictive attempts at comedy, which rouse laughter with a snarl. She is rooted in one dear perpetual place, a place that is treasured because she is there, and that is perpetual because she has bestowed upon it a love which does not wither.

Something else happened in June, 1919, and I should be much surprised if Yeats did not have it in mind. The United States Senate approved the nineteenth amendment to the Constitution, granting to women the right to vote. I have read several of the arguments for and against. One of the common predictions of those in favor was that women would leaven the political world with their idealism, their good sense, their care for the weak and vulnerable, and their aversion to hatred and violence. That was just Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in pink ribbons. Experience has shown otherwise. No one will dare to say, “Women are now involved in politics more than ever before, and therefore we have become less polarized, less angry, more determined to accomplish difficult projects for the common good regardless of which party benefits, more patriotic, and more devoted to our intellectual and artistic heritage.”

The opponents, for their part, worried that the political would overrun the private. Instead of having half of the adult population immune from political interest, so that families could remain friendly with one another despite whom the men were voting for, we would have the whole nation wound up to a fever pitch. There would be no “Gregory’s wood and one bare hill” anymore, and the storm would blow down every roof and haystack in sight: every protection against hatreds, and every reserve against the social winter when it comes. Women would not make politics sweet. Politics would make women sour. The road paved from the hearth to Congress would bear the rolling tanks of intrusion and conquest from Congress to the hearth. Surprise, surprise.

I am not saying anything specific here about the suffrage, given our current economics and way of life. But I am trying to think with the mind of the poet Yeats, to understand how he could write what would cost him his job, if he wrote it now, and what will strike indulgent readers as merely sentimental. It is not. It is a gage flung down against the modern world. It is a direct assault against what in “The Seven Sages” he calls “Whiggery,” a “levelling, rancorous, rational sort of mind / That never looked out of the eye of a saint / Or out of a drunkard’s eye.” There is to be no such intellectual leveling or political rancor in his daughter’s life, but rather custom and ceremony, the antithesis to each, and what we now thirst for, without knowing what they are:

And may her bridegroom bring her to a house

Where all’s accustomed, ceremonious;

For arrogance and hatred are the fares

Peddled in the thoroughfares.

How but in custom and in ceremony

Are innocence and beauty born?

Ceremony’s a name for the rich horn,

And custom for the spreading laurel tree.