In a Wall Street Journal column from September 2016 (“The Politics of ‘The Shallows’”), Peggy Noonan noted that the young journalists and politicians she has met lack the “deeper understanding” that comes from long hours of reading. “They are college graduates,” she said, “they’re in their 20s and 30s, they’re bright and ambitious, but they have seen the movie and not read the book.”

"We have become so accustomed to the blasé attitude toward our writers that we don’t realize how odd it is. Other nations honor their writers as national resources..."

The column stayed with me because the point was so obvious but rarely asserted. Books and literature used to saturate mass culture in America so much that even if you were not a bookish type, you still picked up literary culture in school, on television, and in public affairs. On any given night back in the 1970s, Johnny Carson would end The Tonight Show with an author and his new book. Twenty years earlier, Senator John F. Kennedy wrote Profiles in Courage, a biography of U.S. senators who in the past took principled but unpopular stands and paid the price. It was a bestseller, won the Pulitzer Prize, and helped propel him toward the White House. When I teach the Beat Generation, I play a YouTube clip from the late-‘50s of Jack Kerouac on The Steve Allen Show reading directly from one of his books while Steve Allen plays soft jazz piano. The pace is gentle; the text Kerouac reads sad and cosmic. Allen disappears as the quirky writer expounds his vision. One can hardly imagine any talk show host today turning his microphone over to a novelist for a three-minute recitation like that, but American society would not be in such degraded condition if leading entertainers and politicians paid more attention to literary culture past and present.

Not long ago, while in the offices of a national education group I was visiting, a photograph on the wall drew me up short. It was a black-and-white image taken with a wide-angle lens, dated November 14th, 1962. The view covers the interior of a crowded sports arena, the camera set halfway up in the stands. The basketball goals have been pushed to the side and rows of chairs have been laid out on the court in front of a platform and podium where a grey-haired man stands alone. The seats on the floor are filled, and so are the bleachers all the way to the top. The quality of the film is crisp enough for you to make out the faces and clothes of individuals nearby, young ones, mostly, intent on the personage below. There must be 10,000 people in all. The place is University of Detroit, the man Robert Frost.

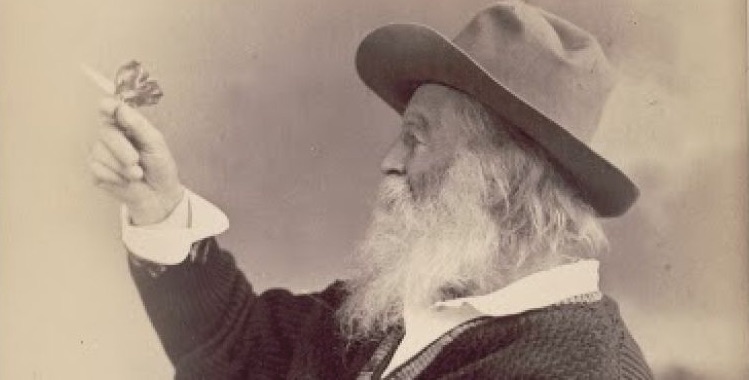

Six years earlier, the same thing happened when T. S. Eliot delivered a lecture at the University of Minnesota. The event had to be held in the sports arena in order to accommodate the 14,000 people who attended. Compare that outcome to what would take place in 2019. If you gathered five of the most distinguished poets and critics in America for a reading at the University of Minnesota, or at any large institution, you would be lucky to garner 200 undergraduates. Who cares what poets have to say? Who regards novelists as major voices in and of America? When Mark Twain died on April 21st, 1910, the New York Times devoted several stories to him for three days after, including tracking down the boyhood pal who served as the model for Huck Finn. One reporter stated, “it has seemed almost impossible to realize an America without him.” A few years later, Ezra Pound summarized Walt Whitman in three words: “He is America.” A few years after that, a reviewer of The Age of Innocence in the New York Times wrote, “Mrs. Wharton is a writer who brings glory on the name of America” (“As Mrs. Wharton Sees Us,” 20 Oct 1920). The same year, Sinclair Lewis began Main Street with a coda on his Minnesota setting that opened, “This is America—a town of a few thousand, in a region of wheat and corn and dairies and little groves,” and nobody thought it presumptuous of him to claim a national significance to his own writing.

At this point, however, to speak of that old-fashioned author figure sounds quaint. I have a mass market copy of John Updike’s The Same Door, a story collection published in 1964. The back cover shows other Updike titles with the exhortation, “KEEP YOUR EYE ON CREST BOOKS FOR THESE BRILLIANT BESTSELLERS BY THE MOST SIGNIFICANT YOUNG WRITER OF OUR GENERATION.”That identification of a writer with a whole generation may have ended in 1991 with Douglass Coupland’s Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, just before the personal computer took off. I have two other mass market paperbacks on my desk, James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity, both of them entries in MURDER MYSTERY MONTHLY. They don’t have a copyright page, but it seems they date from World War II, as the inside cover of Postman begins, “Today publishers as well as shipbuilders have their part to contribute in our all-out Victory effort.” The second paragraph of that statement turns to reading in general with a series of charmingly naïve claims.

Reading is one of the great morale builders. Reading helps clear our minds, hold on to our sense of humor, and establish a fresh and new perspective in dealing with our problems. The publishers of MURDER MYSTERY MONTHLY are trying to do their little part in helping a fighting nation to secure that mental stimulation and enjoyment that disperses fatigue and makes for happier and better fighting men and women.

This is promotional copy, of course, but that only emphasizes the status of reading in a pre-screen time. Our sophisticated elites may laugh at the earnestness, but it certainly helped sustain a vibrant literary scene that produced not only top-rank artists such as Ralph Ellison, but also dozens of skilled craftsmen such as Cain, Raymond Chandler, and Ross Macdonald, three of the best genre fiction writers of the time.

We have become so accustomed to the blasé attitude toward our writers that we don’t realize how odd it is. Other nations honor their writers as national resources—Yeats in Ireland, Pushkin in Russia, Basho in Japan . . . The German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel began his lectures on aesthetics precisely with the national meaning of great expression. “It is in works of art,” he wrote, “that nations have deposited the profoundest intuitions and ideas of their hearts; and fine art is frequently the key—with many nations there is no other—to the understanding of their wisdom and their religion.” To appreciate Athens, we read Sophocles; Rome, Virgil; Olde England, Chaucer . . . Edvard Grieg was a composer, not a writer, but he has a stature that makes Norwegians say, when they hear Peer Gynt, “This is ours!”

Many years ago I spent a summer in Paris and I got to know an Italian motorcycle cop also staying in the pensione where I was. I took French classes at the Alliance Francaise; he was enjoying a few weeks of vacation. We grabbed an ice cream after dinner and visited a museum now and then, both of us trying to converse with waiters and clerks in our bumbling French. One evening, after an exchange with a supercilious Parisian bartender, he pulled me aside and growled, “These French, they think they’re so superior . . . 2,000 years ago while we were building the Colosseum and writing The Aeneid, they were living in caves and”—at this point he raised his right hand, rubbed his thumb against his fingertips, and scrunched his face in disdain—“eating with their fingers!”

I laughed, but took a lesson. He, a working-class guy, rugged and husky, carried Virgil within him as a point of inherited joy. The Italian past gave him confidence. I, a teacher of American literature not long out of graduate school, studied the greats but was not encouraged to remember them that way at all. It was the ‘90s, and the going method among young literary scholars was to draw out of classic writers their illiberal notions, Emerson’s racism, for instance, or to highlight their critique of American society (e.g., Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson). There was an irony in that approach that my colleagues did not care to consider. For, writers and critics in the mid-19th century believed that America would really come into its own and join the ranks of civilized nations only when it produced a distinctive literature of its own. Greece had Homer, Rome Virgil, England the Arthurian legends and Shakespeare . . . America needed epic creations it could claim as native, Emerson said in “The Poet” and Whitman in the Preface to Leaves of Grass. A national literature would foster an upright and healthy nationalism.

Which explains why the cultural left has spent the last 50 years dismantling an American literary canon. In the name of diversity and multiculturalism, they have taken down the old year-long course in American literature that I took in 11th Grade and which ran from the Puritans and Ben Franklin to the Modernists Faulkner and Fitzgerald. Instead, English high school teachers have a Chinese menu of classic and contemporary, Dead-White-Males and woman writers and persons-of-color, from which teachers pick as they fill out their syllabi. The result is that a common core of American literature no longer exists. In my freshman classes at Emory University, filled with AP and Honors students, there is only one book that I can mention and be certain everyone has read it: Harry Potter.

And that was the aim of the academic left—to break up American literature by diversifying it to the point that there was no center any more, no tradition. They may have claimed another goal, that is, to introduce more non-Dead-White-Male authors into the syllabus and render a richer and more accurate version of American literary history, but that deeper and fuller understanding has never arrived. Undergraduates have less sense of American literary history than ever. Richard Wright and Edna St. Vincent Millay are less familiar now than they were in 1980. In other words, the goal has been reached, not greater knowledge of a more diverse canon, but no coherent knowledge of any canon.

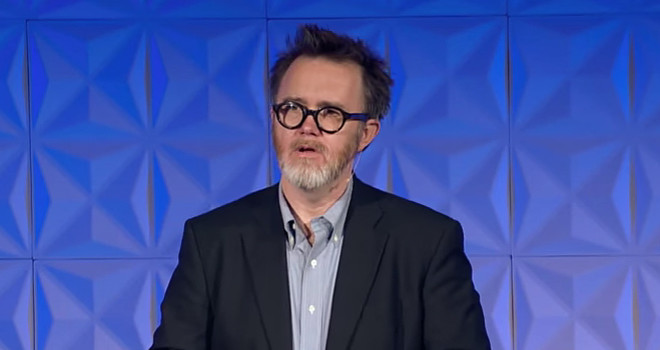

They succeeded, yes, and the right in America showed itself utterly incapable of stopping them. I have seen it over and over, conservatives in high stations outgunned and outmanned on cultural grounds, or, perhaps, unaware that this battle needs to be fought. At the National Conservative conference in Washington D.C. last summer, I do not recall a single word about the value of a national literature. Nationalism, to most of the conservatives in the public sphere, is a political and social formation, not a cultural one. But what is a nation in the modern world that cares little about the best users of its language?