Whiteness Studies is one of the most influential academic disciplines to emerge in recent years. Regarding whiteness as a centripetal ideology that upholds white supremacy and so-called institutional racism, this doctrine treats the de-centering of whiteness as the most crucial objective in the critical evaluation of social norms and institutions. Whiteness Studies, I have argued in an essay for Areo, falls prey to the reification fallacy. It succumbs to another logical fallacy, however, this one resulting from the presumption that the origin of an argument determines its quality. This is known as the genetic fallacy, which Whiteness Studies scholars[1] have used to brand individualism and objectivity as ideologies of white supremacy.

"Whiteness Studies must be resisted, because it leaves us in the dark of Plato’s cave, without the tools of reason and evidence to make our way out into the light. Only indoctrination, and its twin sister intolerance for dissent, are permitted."

The postmodern Weltanschauung of twenty-first century social justice activism reduces matters of conscience to an analysis of power and privilege and to their effects on so-called marginalized groups. Social justice activists are obsessed with dominant discourses as key determinants of what people take to be “true.” As they see it, it is Power that makes things “true,” and so any ethical claim cannot be understood as true in itself, but “true” only per the criteria furnished by dominant discourses. Now this is obviously a strange situation. If reason, science, and Enlightenment are rooted in historical contingencies that give rise to claims that have no inherent “truth” value, then, by the same token, the concerns of contemporary social justice activists themselves about power and privilege are rooted in twenty-first century contingencies that give rise to claims which have no inherent “truth” value. Thus, however indignant about this or that, the social justice activist represents just one vying discourse among others.

So, where is the way out of this mess? Actually, none is needed. You see, the moral sanctimony with which social justice activists denounce even the slightest indiscretions reveals a double standard and a smuggled-in notion of objectivity: Social justice puritanism is on the “right side of history,” while reason, science, and the Enlightenment—however much they may have contributed to human progress—are remnants of eighteenth-century obsolescence, and should be denounced as enablers of slavery and colonization. In short, social justice activists want it both ways.

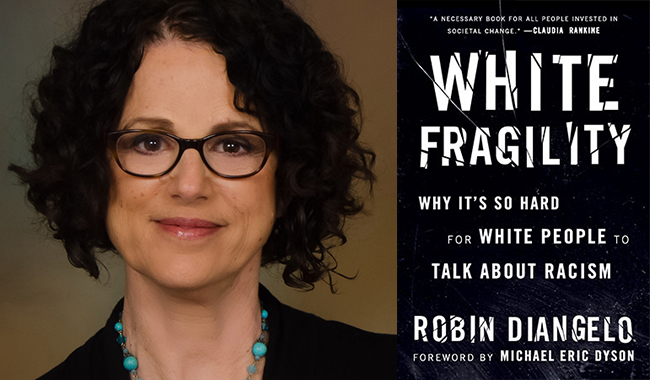

We see this in Whiteness Studies, which, according to Douglas Hartmann, Joseph Gerteis, and Paul R. Croll, authors of a paper entitled “An Empirical Assessment of Whiteness Theory: Hidden from How Many?,” has “swept across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities and social sciences, and into wider mainstream attention.” Consider, for example, the theory of white fragility, a main derivative of Whiteness Studies and the brainchild of social justice activist Robin DiAngelo.[2] White people, this theory asserts, are hopelessly socialized into implicit biases, such as belief in individualism and in objectivity, and these evils reinforce a culture of white supremacy. So pervasive has this “racialized” consciousness become, says DiAngelo, that “even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves.”

As I have argued[3] in several outlets, there are many problems with this sophistry. One is the insidious way in which it reframes the conversation around race so that it becomes impossible to interrogate DiAngelo’s ideas without being accused of fragility. DiAngelo, and Whiteness scholars in general, hold that whiteness is so invisible to white people that they are simply not equipped to challenge white supremacy. This ideological blindness precludes white people from having any meaningful insight into the nature of racism—unless they are prepared to defer to academic theorists on what Hartmann et al. describe as the core tenets

of critical whiteness studies: specifically, those relating to the purported invisibility or taken-for-granted nature of white culture and identity; the understanding (or lack thereof) of white privilege; and adherence to color-blind, individualist ideals that may serve to obscure both identity and privilege.

So, one must submit to indoctrination in the precepts of Whiteness Studies, and to the theory of white fragility in particular, or else remain in a state of unearned privilege and fragility.

Meanwhile, Whiteness scholars show no interest in exploring conceptual ambiguities and empirical shortcomings that might emerge from any rigorous unpacking of intricate ideas like individualism, objectivity, identity, color-blindness, and white privilege. Concerns about whether the core tenets of Whiteness Studies are conceptually sound, empirically verifiable, or falsifiable are therefore dismissed as exhibitions of white fragility. The upshot is a handy fragility trap arising from a conceited presumption of infallibility. Armed with this disingenuous method, DiAngelo and the rest can dismiss any objections to their core tenets—or indeed to any other aspects of Whiteness Studies—on the assumption that such objections are invalid because they are made by a “defensive” white person helplessly steeped in the invisible ideology and discourse of whiteness.[4]

The fragility trap thus succumbs to the genetic fallacy, explicitly manifest in the refrain that’s according to you, one I have often encountered when raising objections to the theory of white fragility. But, as I pointed out in my essay “Social Justice and the Critique of Reason,” published at Areo on February 4, critical theory did not raise “questions about whose rationality and whose presumed objectivity underlies scientific methods.” Rather, as Max Horkeimer shows in his Eclipse of Reason, critical theory was concerned with the instrumentalization of reason itself in the age of industrial capitalism.

We can take DiAngelo at her word when, in the first chapter of her best-selling book about “why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism,” she writes: “[W]hen I talk to white people about racism, their responses are so predictable I sometimes feel as though we are reciting lines from a shared script.” Of course, the idea that white people do not like to be called racists—or to be accused of racism or of complicity in racism—is not a unique insight. Psychological defense mechanisms are common in human nature. Nor is it surprising that white people are skeptical about a transformation in the way they are supposed to understand racism that presupposes their culpability, even if they are not immediately able to defend their skepticism. I see no reason to doubt that many of the reactions of white people reflect knee-jerk sensitivities rather than reasoned arguments that weigh and consider the premises and evidence. But I also suspect that many of the reactions of white people reflect a sound intuition that studying racism should not be about indoctrination but about dialogue, debate, and rigorous examination of first principles.

In any event, skepticism is certainly warranted, given how much Whiteness scholars take for granted. For example, Hartmann et al. found that “one of the most frequent and important criticisms [of the discipline] involves the empirical grounding upon which the claims of whiteness scholars are based.” “[M]any critical race scholars,” they go on, “are fundamentally skeptical of (if not simply opposed to) quantitative data and techniques to begin with.” In addition, in a compelling critique of Whiteness Studies and its historiographical application to the study of labor history, historian Eric Arsenen writes that the field “suffers from a number of potentially fatal methodological and conceptual flaws.” One is that “whiteness has become a blank screen onto which those who claim to analyze it can project their own meanings.”

Finally, owing to the postmodern Weltanschauung, the principles of white fragility theory, and of the core tenets of Whiteness Studies from which it is derived, send critics around and around in a closed epistemic circle. One might wish, then, to just give up and never bother again with critical race theory. Yet this would be a mistake, for having suffused the culture, critical race theory is terribly influential. Examples abound and seem to increase by the day. For instance, in a March 25 article for The Paris Review, Venita Blackburn, assistant professor of creative writing at California State University, Fresno, argued that “White People Must Save Themselves from Whiteness.” In an April post on her WordPress site, MIT librarian Sofia Leung wrote that “library collections continue to promote and proliferate whiteness…by taking up space in our libraries.” Such hysteria spreads throughout the culture, and there is no telling whom or what it might influence.

The paradigm has even inserted itself, as an introductory warning, into a book entitled Kant’s Critiques (A & D Publishing; 2008). “[T]his book is a product of its time and does not reflect the same values as it would if it were written today,” the warning proclaims, adding that “[p]arents might wish to discuss with their children how views on race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and interpersonal relations have changed since this book was written before allowing them to read this classic work.” Well, Kant’s philosophy, like all philosophy, was in part a product of its time, and Kant held some views that many of us find objectionable. But this has nothing to do with why we read Kant or why his work is important. Nor will identity politics help one bit in understanding Kant’s argument for the synthetic a priori or argument for the categorical imperative.

Kant’s philosophy was a reaction, in part, to the epistemic skepticism of David Hume, notably regarding our understanding of causality. It also addressed the “crisis of the Enlightenment,” trying to reconcile a mechanistic conception of nature to reason as the basis of freedom and morality. Thus, one would be better prepared to delve into the intricacies of Kant’s philosophy by reading up on Hume in particular, and Enlightenment thinkers in general, than by reflecting on the values of modern identity politics. There is no reason to dismiss or reevaluate Kant on the grounds of presentism simply because he did not fully adhere to the moral standards that prevail in our own time. And it is the height of arrogance to presume what Kant would believe if he were alive today. It is also terribly ironic in a philosophical context.

Individualism and objectivity, it goes without saying, are not tools of white supremacy. As philosopher Michael Ayers explained in a discussion with Bryan Magee on the philosophy of John Locke, an “individualistic view of knowledge” is simply the view “that nobody else can do my knowing for me…I have to think things out for myself in order to have knowledge.” Individuals are capable of reasoning through an argument objectively in order to evaluate a claim about, for instance, the evils of racism. To dismiss individualism and objectivity in favor of an evaluation of a claim that rests on the speaker’s group identity is a surrender to the genetic fallacy.

If individualism and objectivity leave a white person incapable of understanding the evils of racism, it is reasonable to ask whether he is ever capable of understanding those evils. Similarly, does the “victim” status of blacks and other minorities exempt them from the common obligation to present evidence and make coherent, context-based arguments? Or can they just assert what they are “owed,” qua “victims”? For all their trendy relativism, the value judgments of postmodernists rely on an implicit concept of objectivity—and yet how easy it is to ignore the need for common standards and consistency when the ends of resentment are in view. In this situation, “victim” groups have a rather convenient license to do what they will to their “oppressors.”

Whiteness Studies must be resisted, because it leaves us in the dark of Plato’s cave, without the tools of reason and evidence to make our way out into the light. Only indoctrination, and its twin sister intolerance for dissent, are permitted. To get a sense of the grave consequences, consider the controversy that arose when, as reported by the New York Post on May 20, New York City Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza implemented mandatory bias trainings “targeting a ‘white-supremacy culture’ among school administrators…by disparaging ideas like ‘individualism,’ ‘objectivity’ and ‘worship of the written word’.” “New York City’s public-school educators,” the Post reports, “have been told to focus on black children over white ones — and one Jewish superintendent who described her family’s Holocaust tragedies was scolded and humiliated, according to firsthand accounts.” Even if well-intended, such phenomena are egregiously unfair, and sure to inspire profound racial resentment.

Locke, Ayers reminds us, thought that in areas like ethics

people ought to spend time, and ought to be given the time to spend, on thinking things out for themselves as far as possible, and if you have that, coupled with a very strong sense of how difficult this is, how hard it is to get things right, then you’ve obviously got the recipe for a tolerant society.

Some of us, thankfully, still take this salutary perspective for granted, but it was long in the making and far from being taken for granted in Locke’s day. And if we want to be a tolerant society, Whiteness Studies and the other powerful resentments of our time cannot be allowed to run their insidious course.

Notes

[1] For example, Robin DiAngelo, who coined the term “white fragility” in a paper that eventually became a book, White Fragility: Why It’s so Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, in Racism without Racists.

[2] Co-author of Is Everyone Really Equal?: An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education. This influential book is required reading in many university courses.

[3] See “The Problem with ‘White Fragility’ Theory,” “The Epistemological Problem of White Fragility Theory,” “What Can a Jeopardy! Episode Tell Us About White Racial Illiteracy,” “Social Justice and the Critique of Reason,” “The Theory of White Fragility: Scholarship or Proselytization?,” “White Fragility Theory Mistakes Correlation for Causation,” and “Whiteness Studies and White Fragility Theory Are Based on a Logical Fallacy.”

[4] A classic example of the Kafka trap: “A sophistical rhetorical device in which any denial by the accused serves as evidence of guilt.”