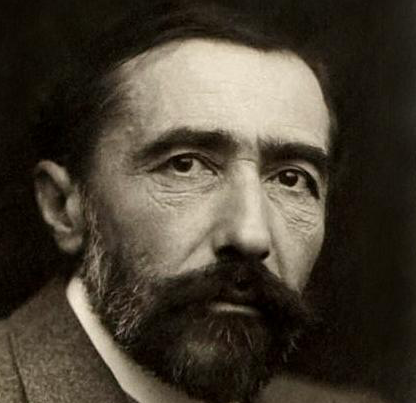

Few people agree with my opinion that Joseph Conrad was the greatest British novelist that there has ever been, but everybody must accept he was the greatest British novelist to have been born in Poland. Józef Korzeniowski was born in Berdyczów, or what is now Berdychiv, in Western Ukraine. His father was a poet, and a playwright, and a revolutionary activist in the times of partition. The family led an almost itinerant lifestyle as they moved around in search of work or to pursue clandestine activities. At one point they were exiled to Vologda in Russia after Korzeniowski pere was charged with being a member of the underground resistance.

"As both an exile and a traveler Conrad saw the world as it was, without the biases of attachment or enmity."

The young Józef loved to read, enjoying in particular the works of Mickiewicz and Słowacki. If there is a word that no one would apply to the books he produced in his adulthood it is “romantic”; yet he loved the poems of the Polish Romantics, both as literature and as political propaganda. Even after he left his homeland, these poets would remain influential on Conrad, though the undying optimism of Mickiewicz would harden into a sort of principled despair. Richard Niland wrote in Joseph Conrad in Context:

Conrad believed his exposure to the Polish romantics and their concern with history gave his own writing its inimitability. In a letter to R.B. Cunninghame Graham, Conrad wrote: "I look at the future from the depths of a very dark past and I find I am allowed nothing but fidelity to an absolutely lost cause."

Another of the youthful Korzeniowski’s favorite books was Victor Hugo’s Toilers of the Sea, and when he was 16 he moved to France to become a sailor. His first years were difficult and dysfunctional, and at the age of twenty he made a half-hearted suicide attempt. It is probable that he suffered from depression, and in his excellent essay “Joseph Conrad and the Question of Suicide” C.B. Cox quoted him as writing:

I am trying to keep despair under. Nevertheless I feel myself losing my footing in deep waters. They are lapping about my hips...

This was fascinating language for a man who loved the sea. It would be reductionist to propose that Conrad’s dark perspective on the world was the product of a morbid mind, but the black dog on his shoulder must have been an influence.

Korzeniowski joined the British merchant navy and, in time, became a British citizen. He had always had ambitions to write and began to work on the cold, enigmatic novels that would make his name.

Almayer’s Folly came first. The story of a Dutch businessman searching for Malayan gold, it explored the same themes Conrad would mine in his later work: the hubris of man, cultural conflict, and the vast gulf between our existential illusions and remorseless reality. The prose, however, could be downright adolescent. Here is the first sentence:

The well-known shrill voice startled Almayer from his dream of splendid future into the unpleasant realities of the present hour.

The explorative reader forces himself past adjective after adjective, only to face the irksome, unintended rhyme of “unpleasant” and “present.”

Edward Garnett, a publisher’s reader and critic, admired Conrad’s book but thought his English was not good enough for it to be published. Garnett showed the manuscript to his wife, the translator Constance Garnett, who insisted, according to Zdzisław Najder, that Conrad’s “foreignness was a positive merit.” We are perhaps indebted to that wise woman for all the books that followed. Conrad had only learned to speak and write in English in his twenties, and his was a talent that evolved into a leaner, meaner, smarter animal. Over the next five years Conrad produced The Nigger of Narcissus, Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim, books which displayed a startling clarity of language, a keen sense of place and a clear-eyed sensitivity to human (or, at least, male) follies.

Conrad the Foreigner

Foreignness, as Mrs Garnett had suggested, was a virtue of Conrad’s. His prose was less mannered than that of many English authors of the period, and his diverse experiences and influences helped him to create a bold modern style, unique in its sensitivity to place and its unobtrusively experimental forms (such as the fragmented narrative of Lord Jim.)

As both an exile and a traveler Conrad saw the world as it was, without the biases of attachment or enmity. This made him a keener critic of the British Empire than, say, Rudyard Kipling, but also incurred the wrath of post-colonialists for his portrayal of their subjects. It is true that Conrad’s relative lack of contact with Africans made his portrayal of them under-developed; and it is true that some of his language, even if it was of its time, is regrettable: but as Craig Raine pointed out in his illuminating essay “Conrad and Prejudice,” it is no good complaining about the fact that Conrad portrays some Africans as cannibals when some Africans were cannibals.

Edward Said, that talented and destructive critic, admired Conrad as a fellow exile but criticised him for failing to transcend the condescending mindset of European imperialism. One can accept, again, that Conrad’s portrayal of Africans was somewhat simplistic. Yet Said made the opposite error in books such as Orientalism and Covering Islam: using reductionist arguments to portray Europeans as merely racist and third world peoples as merely oppressed. Conrad might sometimes have seen the world in too broad strokes; still, he never wore the blinkers of ideology.

Many of Conrad’s peers never quite accepted him as an Englishman. Though Rudyard Kipling thought him “the first among us,” he maintained that there was something alien about him. “Reading him,” Kipling reflected, “I always had the feeling that I am reading a good translation of a foreign writer.” “I am more British than you are,” Conrad wittily told his friend David Bone. “You are only British because you could not help it.” Yet there was something to what Kipling said. Conrad—unlike, say, the American T.S. Eliot, with his tweeds and bowler hat—made no real attempts to embrace Englishness. He had no sentimentality towards English traditions and English institutions, was largely indifferent towards British politics, and addressed British society with clear detachment.

Nonetheless, he was happy to have made his home on Britain’s “hospitable shores” and used its language as well as anyone. He was a sailor in the world’s foremost maritime nation and had the morbid irony that Englishmen and Poles deploy in dark situations. H.L. Mencken—who liked to project his own opinions onto authors—might have exaggerated the extent to which Conrad employed humour in his work, but he was correct that in Conrad’s books “one hears transcendental mirth, echoing and re-echoing down the black corridors of empty space.” Conrad himself, in his dark assessment of the universe as a machine, wrote:

It has knitted time, space, pain, death, corruption, despair and all the illusions and nothing matters. I'll admit however that to look at the remorseless process is sometimes amusing.

A mischievous academic could do worse than comparing the works of Joseph Conrad and P.G. Wodehouse. In many ways the men could not be more different: one an outsider; one classically English; one a merchant of gloom and another of good cheer; one obsessed with far-flung people and far-flung places and another with the English upper classes. Still, for all their differences, both were preoccupied with the simultaneous arrogance and incompetence of small men in an uncaring world.

Conrad the Pole

Conrad was not, as one might have been forgiven for assuming, a thoroughgoing cynic. In his way, he was a romantic. He believed in the value of Polish nationalism.

In 1914, when the country was still partitioned, Conrad visited Poland, travelling from Kraków to the beautiful mountain town of Zakopane. There, he met Polish artists and intellectuals, and read and admired the works of Polish authors. He was especially enamoured of the novelist Bolesław Prus, whom he proclaimed “better than Dickens.” It is a shame that Conrad had not had a chance to engage with Positivism, of which Prus had been a representative. Prus and other authors believed in the power of scientific rationality, and Conrad was acutely aware of the excesses of both romantic emotion and desiccated reason.

By and large, the Poles were appreciative of Conrad, though he was criticised by Bronisława Dłuska, the sister of Marie Curie, for not using his talents to advance the cause of Polish independence. We cannot know how much Conrad took this scolding to heart, but on his return he was more energetic in promoting Polish interests. He had never lost the desire for his homeland’s freedom. What he doubted were its chances for success. In 1916 he wrote a memorandum addressed to the British Foreign Office. Zdzisław Najder writes in Joseph Conrad: A Life:

Conrad says in the memorandum that Polonism cannot be reconciled either with the detested "Germanism" or with the entirely alien "Russian Slavonism." In spite of her captivity, Poland has survived as an outpost of Western civilisation and the restoration of her statehood is the West's moral duty.

This stirring patriotism was accompanied by prescience:

Poland would occupy a permanent place in the "Anglo-Franco-Russian alliance;" at the same time she could become a kernel of "a League of Northern Powers...forming a barrier against ambitions that are as yet hardly conscious of themselves or to resentments that will not die out for many years after this war.”

Though he missed the rise of communism, Conrad had a sense of Germany’s rebirth before it was beaten. He looked at the future from the depths of a dark past and knew the ending of one war planted the seeds for another. Yet he did not see the bud that would be Polish independence. It was frail, and would be torn and battered, but it was real and he was startled when it burst into bloom.

Visiting Kraków in 1914, Conrad told a Polish audience (according to a letter he wrote later on):

Have no illusions. If anybody has got to be sacrificed in this war it will be you. If there is any salvation to be found it is only in your own breasts, it is only by the force of your inner life that you will be able to resist the rottenness of Russia and the soullessness of Germany. And this will be your fate for ever and ever. For nothing in the world can alter the force of facts

“Nothing in the world can alter the force of facts.” It could have been Conrad’s slogan if he had been crude enough to have one. Of course, Poland’s escapes from partition, Nazism and communism would not come without foreign assistance, but Conrad was right that its freedom depended on the struggles and sacrifice of Poles. He had seen too much of the world to trust the benevolence of foreign powers.

Dłuska had been wrong to have expected Conrad to be a prominent advocate for Poland. The writer was a great artist, not a great propagandist, and the “meanings” that emerge from his novels are the products of his keen-eyed observations, not his desire to change the world. Had he attempted to achieve the latter, one suspects, his writings would not have had the same force. Still, that keen eye made him a useful adviser for the Poles as they prepared their last push towards independence, and his work proves that Conrad never lost his love for his homeland.

Conrad died of a heart attack in 1924. His funeral took place in Canterbury, in a town, ironically for this ambiguously English author, festooned with bunting and English flags. It was the Cricket Festival. His gravestone was marked with his original Polish name, Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, except that some careless Englishman wrote the “Teodor” as “Teador.”

Englishmen went to sea imagining glorious adventure and limitless potential. Conrad went to sea imagining dark hinterlands and human weakness in the face of absurdity. Englishmen thought of home as the proud motherland to which they would triumphantly return. Conrad thought of England as home but also felt the pain of exile from the nation of his birth. It did “other” him, as Kipling thought, but it also made him honest and unsentimental. He was the best of them.